— Provincialism Perfected: Global Contemporary Art and Uneven Development

Looking back on twentieth century modernism from the standpoint of today, it seems that its major aesthetic component was actually provincialism. Across the world, different forms of social and economic modernization emerged, leading artists to develop new practices that broke from tradition to engage with these shifting circumstances. However, the early canonization of “modern art” in Western Europe, followed by the transfer of power to New York towards the middle of the century, meant that most practitioners were inevitably forced to benchmark themselves against external examples. This produced major power imbalances between artists from different nations.

One key text on this issue is the Australian critic Terry Smith’s 1974 essay “The Provincialism Problem.” Smith argued that modernists from outside the international centers were constantly pulled between

two antithetical terms: a defiant urge for localism (a claim for the possibility and validity of “making good, original art right here”) and a reluctant recognition that the generative innovations in art, and the criteria for standards of “quality,” “originality,” “interest,” “forcefulness,” etc., are determined externally.1Terry Smith, “The Provincialism Problem,” Journal of Art Historiography no. 4 (June 2011): 3, →

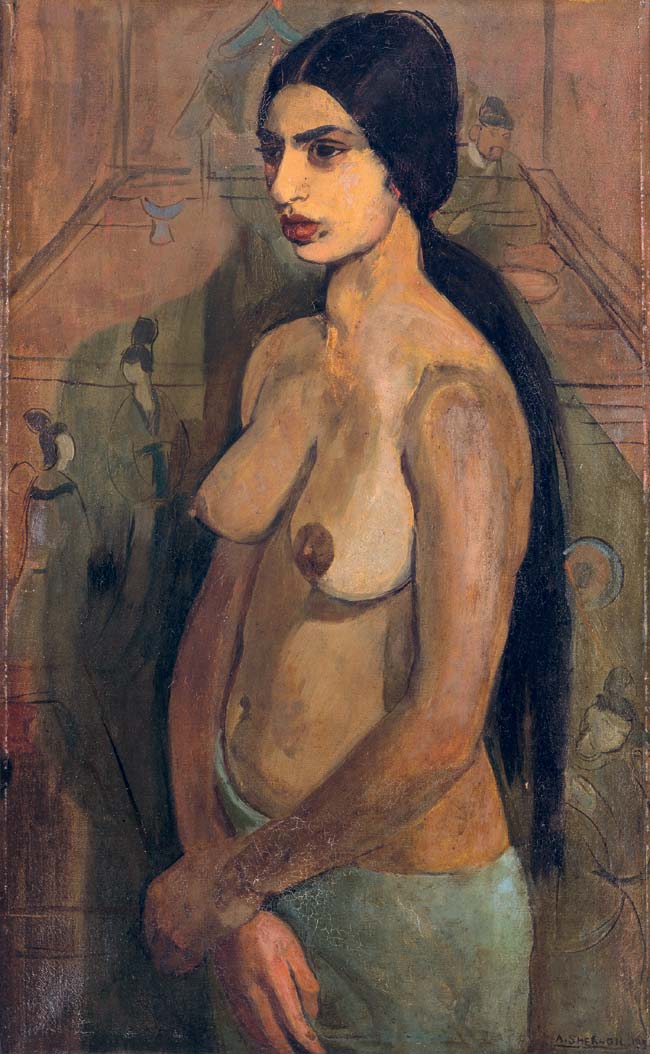

Smith insisted that this was the condition of “most artists the world over,” and that even practitioners living in New York were largely provincial, since “the overwhelming majority of artists here exist in a satellite relationship to a few artists, galleries, critics, collectors, museums, and magazines.”2 Ibid., 9. Nonetheless, the situation was undoubtedly very different for non-Western artists living in colonial and post-colonial situations. Smith remarked that while Jackson Pollock could be internationally accepted as a “great artist,” outside his home country, Sidney Nolan could only ever be received as “a great Australian artist.” This would only be exacerbated in the case of artists from less economically developed nations.3Ibid., 5. Consequently, the many assertions of defiant local modernity that emerged from the “peripheries” throughout the twentieth century demand to be read as critical attacks on colonialism and uneven development.

But in what ways has provincialism altered since 1989? Contemporary art is characterized by aesthetic pluralism, with a great multiplicity of styles constantly sharing the stage. This overwhelming diversity is inseparable from globalization, which sees artists from different sides of the world frequently exhibiting together through an international circuit of institutions and events. Furthermore, as Peter Osborne, Miwon Kwon, and others have argued, contemporary art is largely “contemporary” by virtue of its being international. As Kwon explains, contemporary art is “the space in which the contemporaneity of histories from around the world must be confronted simultaneously as a disjunctive yet continuous intellectual horizon, integral to the understanding of the present (as a whole).” 4Miwon Kwon, “Response to ‘Questionnaire on “The Contemporary,”’” October no. 130 (Fall 2009): 13–15; Peter Osborne, Anywhere or Not at All: Philosophy of Contemporary Art (London: Verso, 2014), 15–22. This can make it appear as if the provincialism problem has been solved, with the structural disconnect Smith identified between local and global having disappeared. Because the international scene thrives on diversity and valorizes cultural difference, in some cases non-Western artists are even permitted entry precisely because they demonstrate their local identities.

However, contrary to being solved, the provincialism problem has actually been neoliberalized. To explain this, we will particularly emphasize three things: continuing disparities in institutional and educational access; the peculiarity of contemporary art’s aesthetics, which can largely only prosper in the very specific educational environment offered by Western art schools; and the shifting “social form” of art practice, which is now primarily structured as an agonistic competition between individualized agents, undermining the formation of collective solidarities.

While the international art world may have no stylistic lingua franca, entry into this arena does require a certain kind of formal complexity. As James Elkins claimed in 2009, there is a “persistence, in current art, of late-modernist values, aesthetic judgments, and assumptions about quality.”5James Elkins, “Response to ‘Questionnaire on “The Contemporary,”’” October no. 130 (Fall 2009): 12.

Despite the absence of necessary materials, techniques, or traits, this question of quality still primarily turns on something profoundly formal: the fostering of a certain auto-reflective, self-critical torsion within the work. Artworks are expected to induce a kind of “dissensus,” deferring the closure of meaning and opening space for reflection.6For a strong critique of this idea, see Suhail Malik and Andrea Phillips, “The Wrong of Contemporary Art: Aesthetics and Political Indeterminacy” in Reading Rancière: Critical Dissensus, ed. Paul Bowman and Richard Stamp (London: Continuum, 2011), 111–28.

Far from a “natural” component of art practice, this is a very specific type of formal complexity, which can only be cultivated amongst significant numbers of practitioners through a particular form of education. Indeed, this is precisely what most Western art schools teach—students are encouraged to undertake independent research (to deepen and specify their work), but are also taught to develop rich connections between theory and practice, as well as process and product. The overwhelming concentration of this particular form of education in Western art schools means that while in principle artists can hail from anywhere, in practice they usually have to pass through certain key geographical hubs.

This great migration of contemporary artists is also due to the connections with galleries and other institutions that students are able to foster in “global cities.” While it would be untrue to say that young artists in London or Berlin have an easy passage into the upper echelons of the international scene, the opportunities available to them are entirely at odds with those encountered by practitioners in most other locations. Particularly illustrative of this disparity are the visits that curators commonly make to different countries while preparing an international show. These gatekeepers inevitably receive a partial and highly contingent view of any given scene, primarily directed by recommendations from acquaintances and local guides. The suggestions they rely on are rooted in a whole range of personal, political, and artistic factors of which the curator can only be dimly aware. For a whole generation of artists in this city, such occasions are among the few real opportunities for being “beamed up” into the international circuit, despite the fact that this is probably already the primary “imagined community” for which their work is intended.7Benedict Anderson, Imagined Communities (London: Verso, 1989). While some will indeed be mystically transubstantiated from local artists into international artists, most will be overlooked.

The other major factor behind the ongoing unevenness of the international scene stems from the way in which it blocks off collective movements by turning practitioners into individualized competitors. The art world’s endless production of difference is not only due to the cohabitation of diverse national identities, but also a consequence of the way that artists, writers, and curators are forced to jostle for positions within the field. Consequently, while the biennial has so often been discussed as the exemplary site for international contemporary art, the global circuit’s underlying logic is arguably much more fully represented by the culture of residencies. As most artists will only very rarely be able to actively participate in biennials, residencies form a core stage in the development of many young practitioners, often compensating for the lack of infrastructure at state level (although some are also increasingly beginning to charge hefty fees). Residencies offer artists time and space to develop their practices, as well as opportunities to meet people and experience new places, but they are also inevitably temporary. In order to string opportunities together, artists must perennially apply for further places or grants, and while the enforced migrations of the residency circuit might broaden horizons, they also militate against the formation of lasting collective bonds.

Consequently, residency culture exemplifies a general trend within the international scene toward the internalization of precarity, opportunism, and especially individualization into art practice. While twentieth-century modernism was so often characterized in its different national guises by the formation of avant-garde movements, the sociality of contemporary art is that of a dispersed network of competing individuals who never cohere into a historical subject with the capacity for collective resistance. The word “network” is here most productively read in relation to the career-building strategy of “networking.” Individuals certainly come into contact with each other, work together, and engage in critical discussion, but they do so at points of transition along decidedly individual trajectories.

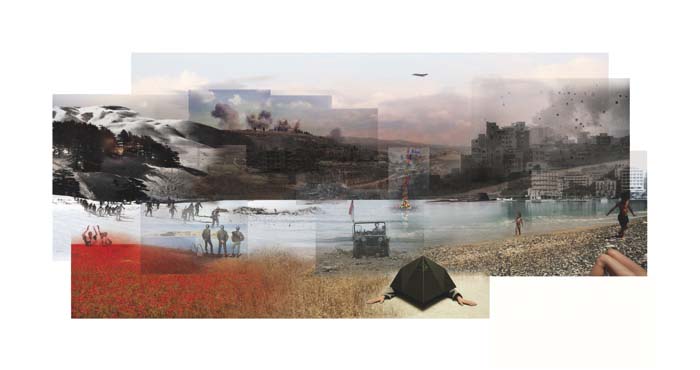

The political significance of this shift in the social form of art practice is enormous. In recent times it has commonly been argued that the globalization of the art world, combined with its aesthetics of critical “dissensus,” have turned the international art circuit into a highly valuable political platform. As Okwui Enwezor and Caroline Jones have suggested, by fostering direct contact between art from different continents, the international scene opens a window onto the contradictions of globalization, allowing the realities of conflict and contestation to emerge from under the illusion of smooth progress.8See Okwui Enwezor, “Mega-Exhibitions and the Antinomies of a Transnational Global Forum,” The Biennial Reader, ed. Marieke van Hal, Solveig Ovstebo, Elena Filipovic (Berlin: Hatje Cantz, 2010), 426-45; Caroline A. Jones, “Biennial Culture: A Longer History,” The Biennial Reader, 66–87. It is easy to imagine why the apparent openness and criticality of the international circuit might appeal to politically committed artists, especially those who lack local platforms for free dissemination and discussion. In this sense the global circuit can be envisioned as a new form of artistic autonomy that is enabled by globalization, but also provides the means to take up arms against this process. However, while the aesthetics of contemporary art may make it a privileged site for critical projects, the socio-economic structure of the international scene means that artists lack any shared political horizon to concretize their affirmations of difference into a strong attack on hegemonic conditions. Without strong solidarities, they are inevitably encouraged to seek individual progress over collective emancipation, leaving very few opportunities to produce structural change.

Far from having been solved, then, the provincialism problem has actually been neoliberalized in two key respects. Firstly, because the unevenness of contemporary art is now hidden by the illusion of individual freedom.9On the contradictory status of “individual freedom” within neoliberal politics, see David Harvey, A Brief History of Neoliberalism (New York: Oxford University Press, 2005), 41–3. In the twentieth century, it was clear that most artists were barred from international success as a result of institutional discrimination. Today, in contrast, it can seem as if artists who do not succeed in gaining a global reputation are either just unlucky or (more likely) let down by their own personal failings. The reality is that the vast majority lack necessary structural amenities, and the global circuit does nothing to provide them. Its principle of stylistic openness operates as a meritocracy, obscuring its own failure to provide infrastructural support with the promise of individual betterment.10 For Marx’s critique of meritocracy, see Karl Marx, “Critique of the Gotha Programme,” in Karl Marx: Selected Writings, ed. David McLellan, 2nd ed. (New York: Oxford University Press, 2000).

Secondly, because so many practitioners are now able to imagine themselves as participants within the seemingly open field of international contemporary art, many take their place in a constant stream that passes through continual rounds of grant applications, residencies, and MFAs, even though it is universally understood that most will never gain entry to the art world’s higher chambers. The individualized career trajectories demanded by this grueling process detract from the formation of regional or transnational solidarities that might provide the basis for infrastructural change. This second form of neoliberalization cuts much deeper than the first. Rather than simply failing to level the playing field, it perpetuates unevenness, catalyzing greater class divides rather than encouraging redistribution. Consequently, ongoing inequalities of institutional access must not be written off as temporary problems that can progressively be ironed out by the movement of globalization. In reality, the international “supercommunity” continues to elbow the sub-communities of local scenes into peripheral status. The conduits connecting the provinces to the global hubs still largely transmit value in only one direction.

×