— TBH IDK FTW

In the spring of 1915 an editorial assistant called Dorothy Parker hung a full-color centerfold of a cadaver above her desk at Vogue. She had pulled it out of an undertaker’s trade rag called Sunnyside. The image was instructive to the novice mortician who might want to learn the best insertion points for embalming fluid, but repulsive to her boss, who soon fired her.

She waited at that desk for news of the world to come. Seeds of information flitting via the thrum of telegraph poles. Stop. Birds on the wires taking flight, feet tickled by the news. Stop. Were these primordial tweets? Stop.

She’d later infer that writing 140-character captions for fashion magazines during wartime led her to believe that civilization was dead.

These and other thoughts were thunk in the presence of information, which she ingested voraciously. Whole books and plays and Hollywood scripts were written against a backdrop of a stack of books and other analog scenery. Printed matter and word-of-mouth were the distractions du jour. She was prolific even through (or perhaps because of) a fug of booze. Sometimes chemical interference is the only thing that makes information feel manageable. A famous American novelist said nothing good is written in the presence of the internet. I don’t agree. But I get it.

I Google “1915 undertaker magazine” and find ads for Esco’s Anti-Odorant Softener and the labels of Ozoform Concentrated Jaundofiant and Control Arterial Hyersol Velva-Glo.

But no cocktail of embalming fluids or fossil fuels could resuscitate this world she declared dead—this fashionable hellscape, this real world.

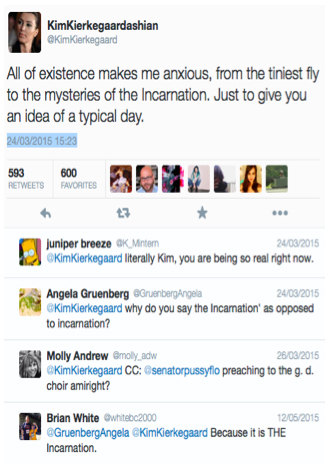

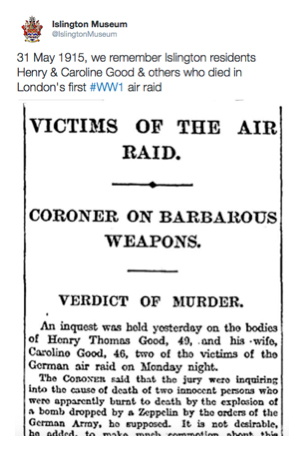

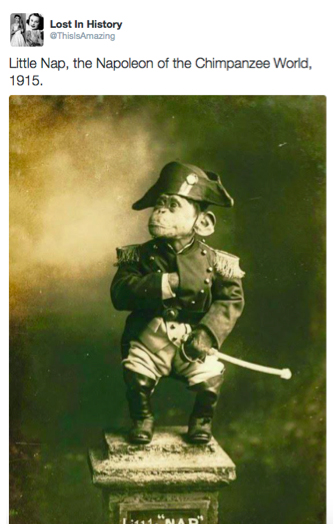

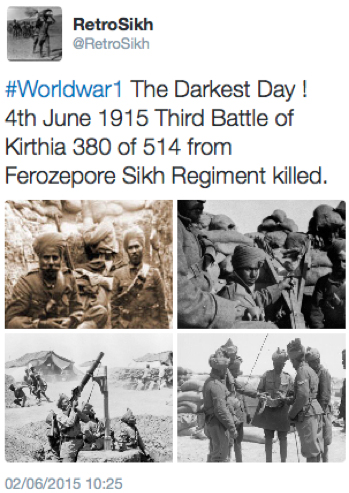

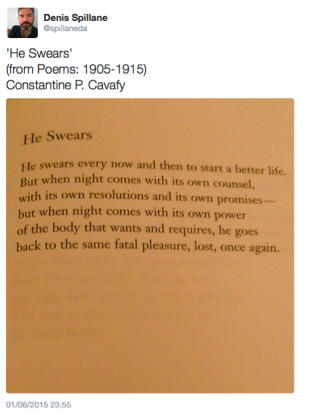

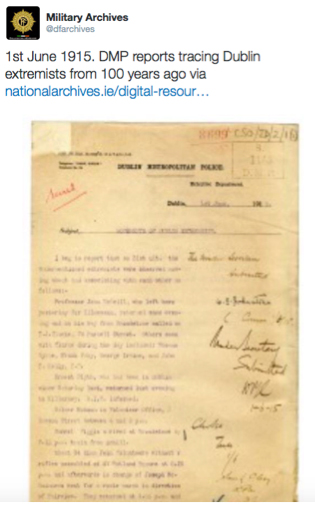

I like to track centennial tweets. They are a social media subgenre. Every day a new fact is dredged up from the swamps of the early twentieth century. Here, have a few:

You see, 1915 AD is MCMXV is the year of the wood rabbit is 1333–1334 Hijri is Taishō 41 See →is Holocene 11915 and Hongxian Year Zero.

This year a zeppelin is dropping bombs on Islington.

There is mutiny in the whispers of the British Indian Army.

A garden in Gympie dies from a drought.

The brakes fail on a train carrying 900 people to Guadalajara.

The Dingbat Family teaches vaudeville how to do the maxixe.

A donkey dies on a road somewhere outside of Zagazig.

The workers of the Bayonne refinery strike Standard Oil in New Jersey.

The Armenian genocide is occurring.

1915 is Dorothy Parker’s second year at Vogue and you can feel the seeping force of trickle-down tragedy.

Fast-forward exactly a hundred years to 2015 and to a new kind of cultural entity called Kim Kardashian. She has had the cover of Vogue. She has 32 million followers. More than Moses. Bigger than Jesus. All that.

Some complain about the Kardashians: that they are TMI on tap.

It’s April and Kim goes to visit the genocide memorial in the global gully called Yerevan. It is a frightening and appropriately austere monument of black marble, and it looks like the unfurling crown of a mother ship at the top of a gray crag of mountains. I was there just a few months earlier, shaken down on the road from Georgia by a bribe-seeking cop in an absurdly high peaked officer’s cap.

We drove through snowy mountains past a chrome-clad UFO as alien as an airstream in these foothills, dead earth dusted with a sugaring of snow and then passed into what we thought was bad weather but was in fact a leaden cloud of pollution, a haze that clutched the city. Is this what Beijing is like on a bad day?

I am invited to the home of an online friend. She is from Nagorno-Karabakh. She grew up in the enclave during the war with Azerbaijan. Once she went with her cousins to fetch water and returned to find their home gone. She now “works in tech.” I tell her I’m a little surprised that the Wi-Fi in Yerevan is so fast and pure and uncut. At least it’s better than anywhere I’ve ever been. We are the same age and knowing her makes me feel inexperienced on this Earth—domesticated by the data I don’t understand.

She says the internet makes her feel the weight of knowing too much. Irritating things. Irrelevant things. Irreverent things. Irrevocable things. But I’m afraid of erasure. The wiped drive of my mind. I know I know nothing. There’s less and less to understand every day. Information ground into digital dust. The world stopped making sense a long time ago. Parker called it before she died on the afternoon of June 8, 1967. Her epitaph reads: “Excuse My Dust.”

And today, on the anniversary of her death, I am in Baku. In order to obtain a visa for Azerbaijan I was required to declare that I hade never visited the formerly Autonomous Oblast of Nagorno-Karabakh. This declaration is an easy one for me but wouldn’t be for my friend. On our way into the city we pass a Zaha Hadid building. It is called the Heydar Aliyev Center. Its banners toast in all caps: “TO THE FUTURE WITH VALUES!” I google him and find he was a KGB officer. A mafioso. An oligarch. A president. He was the amasser of a fortune made of Caspian Sea caviar. And the father of the current president, Ilham Aliyev, who is in turn the father of a teenage boy. It is said this boy owns nine Dubai mansions worth $44 million, which is calculated to amount to approximately “1,000 years’ worth of salary for the average citizen of Azerbaijan.”

A millennium of money.

I visit the Palace of the Shirvanshahs and find myself standing in front of a Shia mosque riddled with one-hundred-year-old bullet holes. A woman stands in front of the thick wall, performing her historical tour as if she is on a stage. “This is where the genocide of Azeris by Armenians happened a century ago. On these stones we are standing on right here.” She calls it genocide. But what is genocide? The noun used always in retrospect—a kind of atrocity in most vital and urgent need of definition. It is not for liberal application. I seek to make sense of this statement online and of course do not find it. Wikipedia clarifies:the Armenian–Azerbaijani War “was a series of brutal and hard-to-classify conflicts.”

This sounds more like the truth.

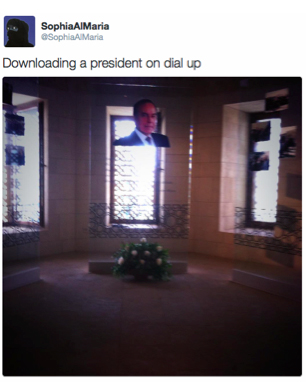

That afternoon I have an encounter with the disembodied bust of Heydar Aliyev.

I tweet this:

It reminds me of the olden days when the internet was slow and you had to trade “phone privileges” for modem time. It also reminds me of a funny story my friend in Yerevan told me about the internet.

Two years ago there was a mass blackout of the WWW in Armenia. Panicked officials couldn’t track down the cause but suspected terrorists or espionage. They followed the cables leading north out of the city and found the problem on an elderly woman’s property, where fiber-optic cables were found severed in the boughs of her tangerine trees. The old woman was uncertain of what she’d done wrong. She had just been out pruning her fruit trees. How should she know she had sliced right through the cords tying Armenia to the rest of the planet? The officials explained to her that she’d broken the internet. A very serious offense. The old woman blinked at them and asked, eyes wet with worry, “What is internet?”

×