— The Idle Monologue of an Unconvinced Surveyor

“It seems that nature has at man’s birth fixed the bounds of his virtues and vices.”

—François de La Rochefoucauld

The idle monologue of an unconvinced surveyor.

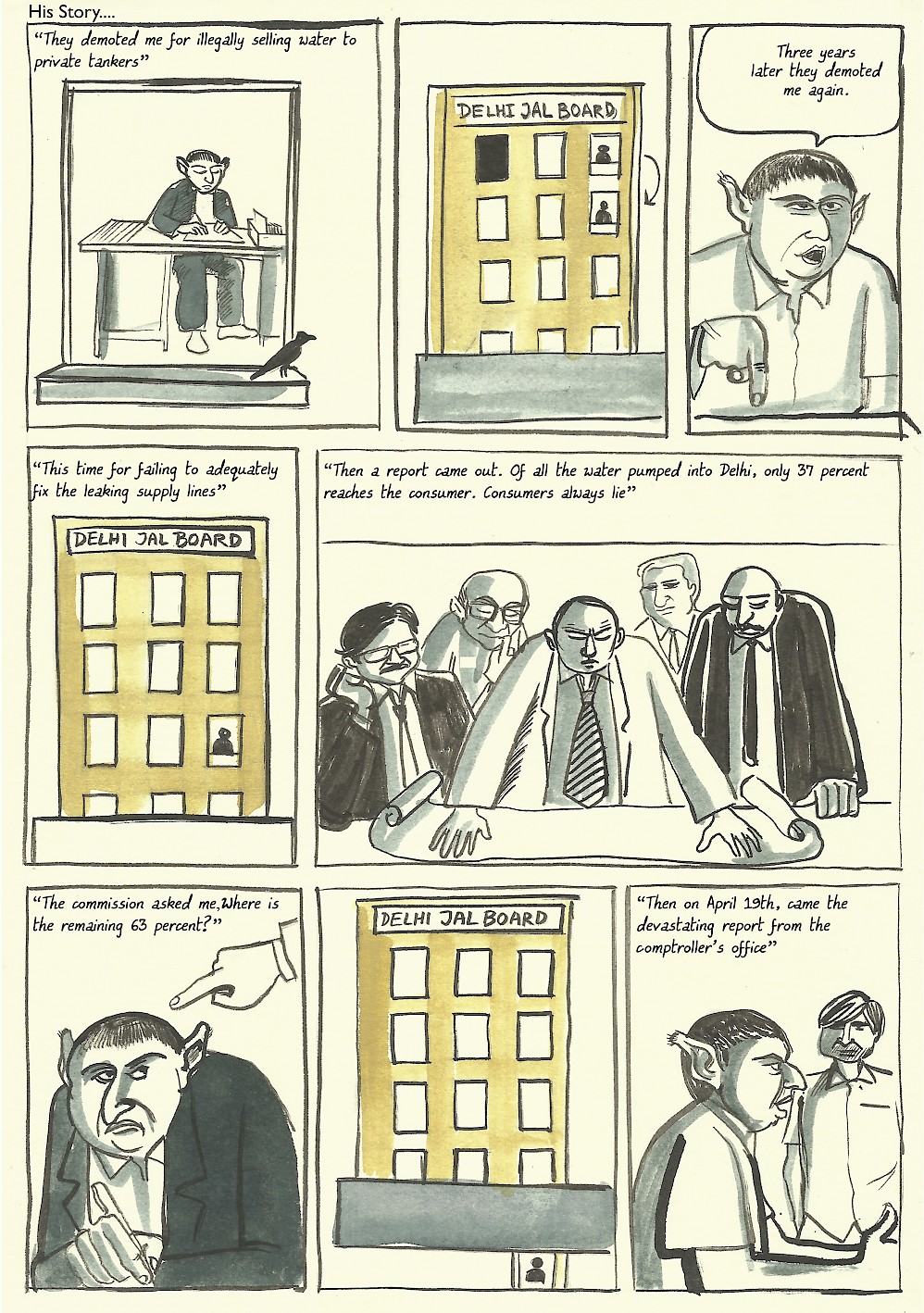

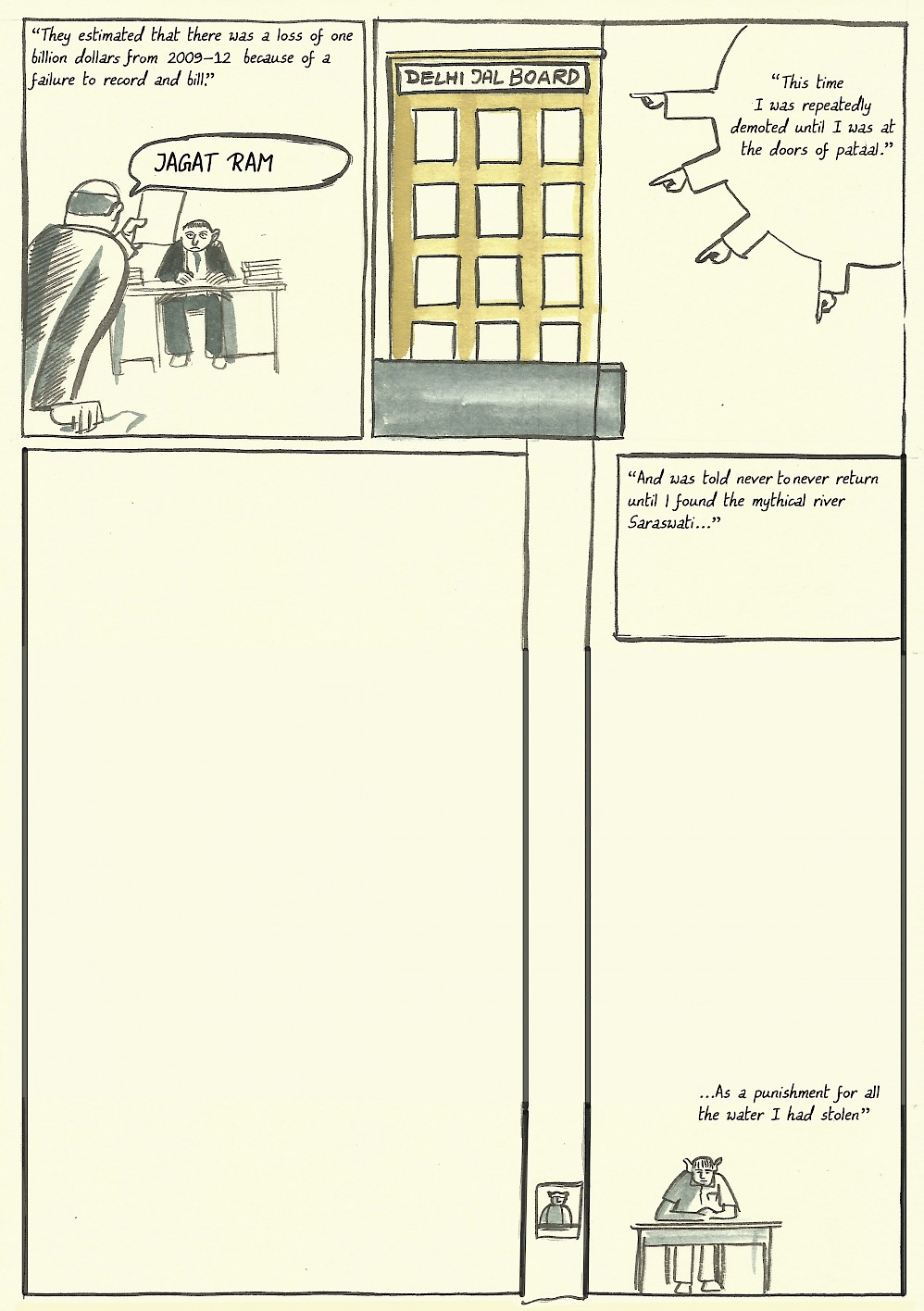

Certain countries have taken the fight against corruption quite seriously. Jagat Ram, a mid-level official at the Delhi Jal Board (the water commission of Delhi), is amongst those who are directly affected.

Bengal’s Derrida, Sukanta Sarkar (alias: Sukantada), who had once suggested minor textual changes to William Blake’s Marriage of Heaven and Hell, had this to say about corruption:

“In certain societies corruption not only should be tolerated but actively encouraged. Corruption is the only viable weapon to fight against unfair rules.”

“More often small people are hauled up on corruption charges while Qatar gets to hold the World Cup, the West continues arming aggressive and unfair nations, and the Iraq War happens despite the whole city of London coming out in protest.”

December, 2008. It was the year India had enforced a ban on smoking in public places. I was waiting for my train to Delhi at Calcutta’s Howrah station.

Unmindfully, I lit up a cigarette in the open-air section of the platform. Halfway through smoking, a railway guard passed by, stopped, retraced his steps, and stood before me.

“Eta ki Hochhey?” Inaccurately translated: “What is this thing that is happening?”

Just then I remembered the government rule, flicked off the cigarette into the tracks, and apologized. As often happens to men with authority, the guard took this as an opportunity to give me a life lesson.

“ ... aar apnara tho educated!” (Translated: “And that too from people like you, who claim to be educated!”)

Banal displays of power are common among visa officers, bureaucrats at the Ministry of Home Affairs, traffic policemen, clerks at government offices, gas agency guys, guards posted by the Archaeological Survey of India, doctors, landlords, staff at the immigration desk, and librarians. One learns from living in India that the best way to tackle such situations is to quietly listen to the person, not make any eye contact, and nod in agreement. Same way as one deals with a headmaster. Never challenge the status quo. But this man was drunk on authority. Unsatisfied by mere naming and shaming, he wanted to hand me over to the station authorities. He wanted me to pay the penalty and get a further bollocking. No problems with that, except I had a train to catch, for which I had reserved a seat one month in advance using sports quota.

So I drew the wicked little man to one corner and requested he settle the matter right there.

“I am sure the railway authorities have other very important matters to attend to,” I reasoned with him.

“Citizen to citizen.

Here’s 500 rupees for Diwali sweets. Donation for the community Saraswati puja.

Eid?

One North Calcuttan to another. Oh! You are from Raniganj, I had a cousin who was once posted there. You want me to be punished, no? Here it is, my hard-earned money. I am unemployed.

Let’s adjust.”

But the man was unmoved.

“Look, my train will leave soon. I will miss the job interview.

My father is a retired government servant.

Are you a supporter of Mohun Bagan

or East Bengal?”

Finally he relented, took the 500-rupee note from me, and left. Phew.

The train was fifteen minutes late. I quashed an impulse to light another cigarette. The December light fell on the tracks, softening the filth. A line of clothes belonging to the platform dwellers swayed in the gentle breeze. Two kids played grab-genitals dangerously close to the tracks. A tea seller made brisk business. Anxious travelers dipped biscuits in their cups.

A few minutes later the guard returned. What now? Wasn’t 500 rupees enough? Could he have changed his mind and wanted to hand me over to the station authorities after all? But I too can say that he took a bribe from me. But he can deny it. Oh no, I don’t have proof. Bribes don’t come with receipts.

The guard smiled at me and handed me a 200-rupee note.

“I think you have given me too much. Three hundred should be enough.”

There is nobility in corruption, although it is difficult to convince the template intellectuals.

François de La Rochefoucauld again:

“We do not despise all who have vices, but we do despise all who have not virtues.”

×