— Look Above, the Sky is Falling: Humanity Before and After the End of the World

Many Amerindians believe that animals have descended from humans rather than humans from animals. Within these cosmogonies, in the beginning everything was human. Then the world ended and from that cataclysm the many species, forests, rivers, stars, and minerals were formed. This dispersion ended the mythic state of primordial cannibalism, when everything was undifferentiated and thus ate its own kin in order to feed itself. All these entities, regardless of their species or form, remain human. There are only some of us who, despite our technologies and sciences, cannot sense the disguised humanity of others. The Yanomami believe that the sky fell on earth and that it had a forest on its back. For the Yanomami, according to their shaman Davi Kopenawa, the sky is in fact repeatedly falling, redistributing this common humanity at each fall. Each falling sky, which is to say each forest, sets in motion a process of sedimentation, metamorphosing some entities while suddenly burying others and transforming them into spirits—perhaps into oil or coal spirits, which wouldn’t be far from the geological explanation of these materials’ origins, or into gold, lithium, or any other of the many rare minerals that energize the earth’s technosphere.1This is a belief that can also be found in other geographical regions, for example among the Kaluli of Papua New Guinea. Déborah Danowski and Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s contribution to this issue of e-flux journal compiles and extrapolates on many similar cosmogonies.

In contrast to modern eschatological visions of the end, the APOCALYPSIS theme of e-flux journal no. 65 follows anthropologist Eduardo Viveiros de Castro’s dedication to such cosmogonies in an attempt to think through and beyond the end of the world. In other words, to think of the end as cosmogony. As the above myths exemplify, our ending is only one of many, and its failing is simultaneous with the (re-)emergence of other worlds, perhaps even, in the words of anthropologist Elizabeth Povinelli, with the possibility of experiencing the world “otherwise.” “There is only one earth,” as the saying goes, but this earth is open to many worlds, mediated by different ontologies, with very different nature-culture dynamics, even in the most ontologically extreme examples with no unsurpassable distinction between nature and culture at all.

Such alternate cosmogonies confront us with two counter-intuitive reversals of modernity’s teleology: that the apocalypse has already happened in the past, and that everything is human. These are vital reversals, for aren’t precisely these categories of time and subjecthood now called into question by the increasing collapse of scales and agencies—of the supposed tameness of nature and the productive agitation of culture in our own societies?

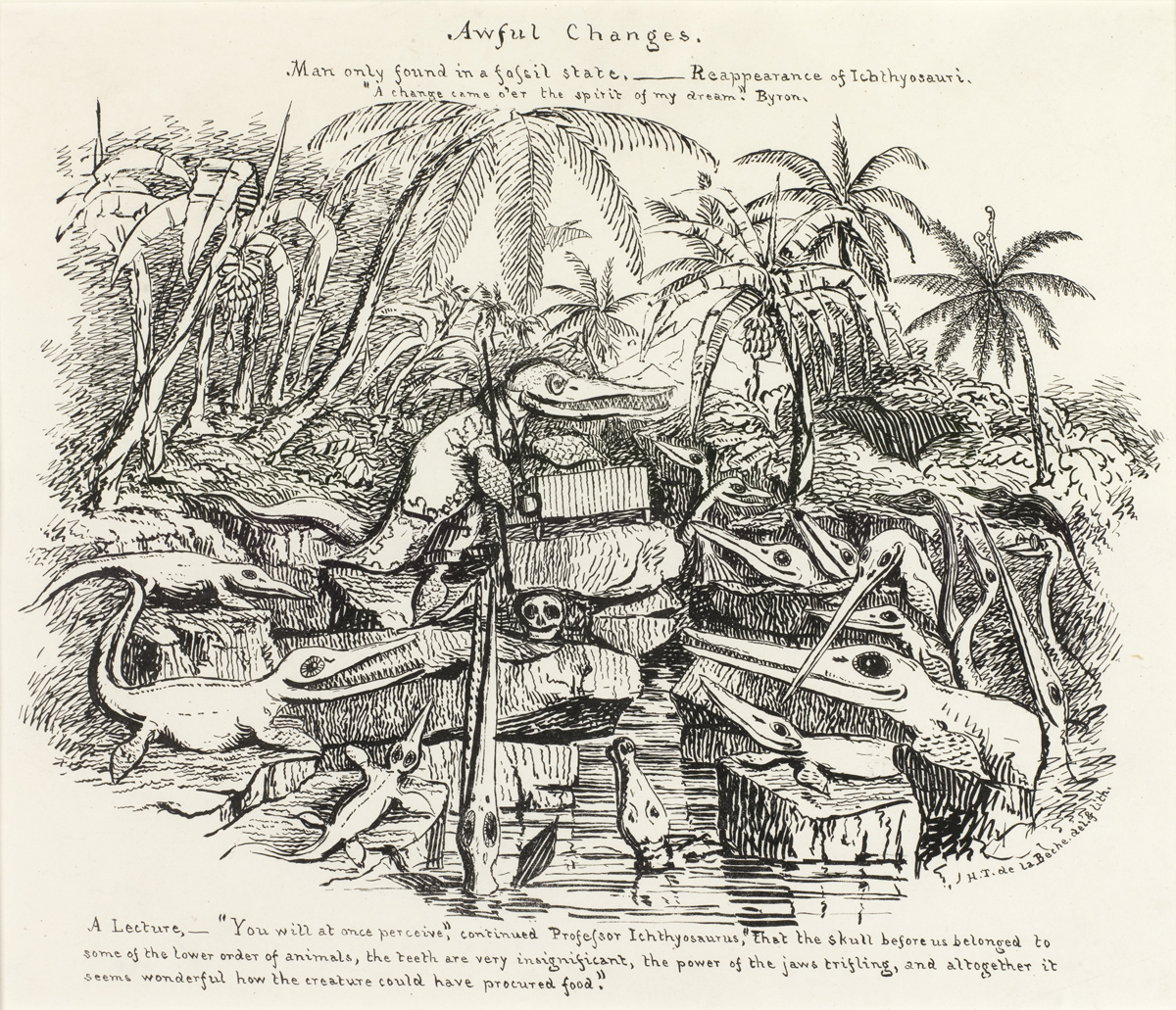

The reverse temporality of these creation myths, which are themselves a negative of Herbert Spencer and Charles Darwin’s evolution of the species, counteract the modern arrogance that our apocalypse must be universal, when in fact the world has already ended for many others, humans and nonhumans alike. It is said that 95 percent of Amerindians died between 1492 and 1610. If for some anesthetic reason the annihilation of more than 50 million people fails to shock, it may give a sense of scale to say that at the time of the first encounters between the Amerindians and Europeans, the Amerindian population far surpassed that of the newcomers.

The first stage of American colonization has recently been suggested as a likely candidate for dating the Anthropocene.2Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, who hold positions in Climatology and Global Change Science in the Geography Department at University College of London, have recently proposed 1610 as the beginning of the Anthropocene. See Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin, Defining the Anthropocene, in Nature, 519 (12 March 2015) 171-180. For a summary see: http://www.cnet.com/news/orbis-spike-in-1610-marks-date-when-humans-fundamentally-changed-the-planet/ The Amerindian apocalypse left large land areas untended by agriculture, including terraforming techniques such as terra preta, or “Amazonian black earth,” the anthropogenic, highly fertile, and carbon-sequestering soil mixture of charcoal, potsherds, manure, and bones that was used by Amazonian Indians. Knowledge of this mixture has recently contributed to an image of the Amazonian forest as being managed by humans, and thus paradoxically to the possible legitimization of nascent geoengineering technologies such as biochar. Hidden in Artic ice cores is material proof that the resulting forest regrowth created a drop in global carbon dioxide emissions—what climatologists Simon Lewis and Mark Maslin call the Orbis Spike.

It is not without irony that a side effect of the positive feedback loop of carbon emissions resulting from this first mass anthropogenic event was the annihilation of part of the world’s population. In saying this, one would do well to remember the centrality of the Americas in the constitution of modernity. Colonial confrontation with Amerindians was vital to the imagination of modernity’s evolutionary progress: wild nature tamed into a future culture of productive rule. The “primitives,” in their state of nature, were the confirmation of the moderns’ civilizational progress; they represented those earlier stages of history from which the moderns evolved.3 Phillipe Descola, Beyond Nature and Culture (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 2010). For the Europeans, the Indians were proof of a culturally and genetically evolving single species—humans—coexisting in the same present. While culture was slowly partitioned from nature, living beings became distinguished both by species and evolutionary chronology. What the Orbis Spike does then is collapse the first unacknowledged anthropogenic event with the birth of modernity’s project of humanity—although ecological symbiosis between humanity and the environment was long acknowledged by the Amerindians in the production of terra preta.

Genocide was the necessary condition behind modernity, and the present neoliberal globalization plan of hegemonic multiculturalism, either in its variations of humanist universalism or capitalist inclusivism, hasn’t changed anything at all. Genocide is also how our modernity ends. Modernity’s rational evolution has ultimately led to carbon cannibalism, radioactive oceans, carcinogenic polymers, and, more recently, fracking and geoengineering, which in reinforcing humanity’s lonely supremacy hold no promise of being much better.

Here, I’m thinking not only of the worlds of indigenous peoples but also of the present rate of animal and vegetable extinction, the highest since the demise of the dinosaurs. This happens at a moment where science’s exponential discovery of exoplanets infuses mankind not only with dreams of a twin earth in deep space but also with Promethean hopes of space colonization and new capitalist frontiers. The question is thus wrongly posed. It is not so much a matter of whether there is life in the universe beyond planet Earth, but rather that we are consciously removing life from the universe: in the universe there will only be the human—and only a very restricted humankind, as the above cosmogonies tell us.

What is ending is the modern world—a very particular world invented in 1492, animated by a naturalist ontology inside of which nature and culture were not to be confused. This is to say that humanity can no longer be taken as the solution to anything—at least not alone, in its enlightened cosmo-ecological ignorance. On the contrary, from the perspective of the earth, humanity looks increasingly like the problem.

And yet this humanity that I am talking about would perhaps be incomprehensible for the Yanomani or the Cashinawa of South America. Theirs is a worldview many would call animist, but which may be better described by what Viveiros de Castro has called “multinatural perspectivism.” To speak of worlds other than ours is not a case of difference in cultures, but of difference in natures. Multinaturalism is the negative of multiculturalism, but more importantly it is the reversal of unitary naturalism. For multinaturalism, nature is not that tamed and complex yet transparent backdrop imagined by the moderns. While nature may be, or used to be, unified for us—and literally by us—for some peoples it is the expression of different embodiments and affects resulting from that primordial diversification.

For such multinatural or animist ontologies, to use the terms of anthropologist Philippe Descola’s global study of the nature/culture divide, humanity is not that Cartesian moral quality that founds modern speciesism.4 Ibid. Rather, as the above cosmogonies exemplify, humanity is the form of a shared, negotiated attribute, transversal to all entities, biological or otherwise. Thus, for the animist worlds of this unavoidably common earth, the problem is not humanity but mankind. Humanity is a totality, yes, but not in terms of species. Humanity is a trans-specific culture, originary and yet differentiated, common yet generative: tortoises and wild pigs that evolved from monkeys, monkeys from man, and tapirs and agoutis even from plants.5 See Claude Lévi-Strauss, The Jealous Potter (Chicago: Chicago University Press, 1988).

This cosmogonic reversal of evolution and speciesism should not be simplistically understood as the refusal of modern science, but as the acknowledgement of the pluriversal explosion of an earth that was called modern for four centuries but which few are certain of anymore.6 The manual guide to both understand and hopefully avoid this thorny path might very well be Isabelle Stengers’s Cosmopolitics volumes. For anthropologists such as Viveiros de Castro, Marisol de la Cadena, Lesley Green, and many others, suddenly the indigenous no longer occupy the blind spot of modernity but are actually pushed to the forefront of this post-apocalyptic world. This is neither Rousseauian idealism nor cosmopolitan escapism. As Viveiros de Castro suggests, it is a matter of learning from their survival and reinvention past their apocalypse, but also a sign of the rupturing vitality of other ontologies in a moment when technocapitalism itself is exhibiting signs of animistic transformation.

And here is the kernel of such apocalyptic dreams. While we may be looking for hybrids to offer us cosmopolitical answers and open post-capitalist horizons, capitalism too is pushing for rupture with itself, defining its new ontology—in a way, creative destruction as world destruction. This poses the question: are we looking at other ontologies, intelligences, and agencies only because capitalism too is transforming itself? This would perhaps be why in the end a shared, immanent humanity might not feel that paradoxical to us. Modernity is evolving out of itself, only to find at the end of its long messianic road those purported slaves of nature it had vanquished, exploited, cultured, be they peoples, with their no-longer-alien natural philosophies, or even animals and plants who suddenly appear to us as subjects in their own right—not in the way of animists, one should add, and not in the way of modernist naturalism either.

Everywhere we look, humanity no longer appears to be the product of modernity but of something other. Humanity untied from the species, for many indigenous animists, or inversely a posthumanity accelerated and hybridized by technology—for Singularitarians, the technocapitalism of AI, or genetic novelty. And let us not forget humanity devoted to one God, earthbound in the Islamic State, with its managerial praise of savagery as regime change, and faith in the iconoclastic power of bodies.7See Abu Bakr Naji, The Management of Savagery: The Most Critical Stage Through Which the Umma Must Pass, trans. William McCants (Harvard: John M. Olin Institute for Strategic Studies at the Harvard University, 2006).

The end of the world is not a multicultural issue but a multinatural one. Fidelity to hybridity is clearly not enough—the same goes for the praise of difference. In contrast to inhuman or antihuman discourses, then, is it possible, like in many animist societies, to suggest that everything is human? Is the word even meaningful beyond the historical meaning the Renaissance gave to it? This would imply a humanity not only beyond the species but also beyond modernity. But what an oxymoron: An amodern humanity? Perhaps in the end these are the wrong questions to ask. To be clear, acknowledging the agency of nonhumans does not make us animist. Animism is simply the anthropological word given to a belief in humanity other than that to which we moderns have been faithful. And yet ontologies change and shift, they confront each other, and must enter into negotiation.8Alongside Isabelle Stengers’s Cosmopolitics series, Phillipe Descola’s Beyond Nature and Culture may very well be the first book of cosmopolitical historiography, at least in the moments in which, in order to think such ontological evolution, it appears to bridge anthropology with historiography. This is what the end, from a multinatural perspective, means: entering into cosmopolitics.

We are now others to ourselves. It is quite clear. Look above: the sky is falling. From this perspective, what we cannot possibly yet see is how the sky has a forest on its back.

×