— A Few Notes from an Extellectual

My Father’s Color Period

“Tonight the film will be broadcast in color.”

A rumor spread in 1979 that the state-owned television station would show a film in color despite the fact that most televisions were black and white. Unlike in cities with Arab inhabitants, the majority of the people in the Kurdish area of Iraq still didn’t have color TV sets.

So my father decided to cut a sheet of colored cellophane and stick it on the screen of our TV at home. It stayed a whole week until he switched it to another color. We used to watch films, music videos, and other programs in a single shade of blue, pink, green, or yellow. Later he began dividing the screen in two, three, or four sections with a different color in each area. We watched figures walking from blue to green, or though yellow to purple to pink.

Eventually, he constructed stripes and other elaborate forms.

After a while, I realized that my father was not the only one making his own color TV. Many other people in the Kurdish area had devised their own unique filters.

Hafiz

Each morning, my father would wake up at 5 a.m. and pace in and out of the kitchen reciting poems. We didn’t know what the poems meant and it was a bit annoying for us, as we couldn’t sleep when he would do this.

Once we asked him what he was reciting every morning.

“These are poems by Hafiz, the great Persian poet,” he proclaimed.

“But I didn’t know you spoke Farsi,” I replied.

“Indeed. I don’t understand Farsi.”

I was puzzled.

He continued: “When I was a kid I was sent to the madrasa. I was one among many other disciples taught by the mullah. Over four years the mullah would teach a group of kids the whole book of Hafiz’s writing. Only after all of the poems were learned by heart, the mullah would teach his disciples the meaning of the words.

“We were the only group with bad luck. We learned the whole book by heart, but then the mullah died. So among all the students, ours was the only group who knew all the poems without understanding them.”

Straight? No, Twisted

In the eighties during the Iran-Iraq War, most people were searching for relatives who went missing in the army. My brother Azad was one of them. Iraqi television told only half the story. Likewise, Iranian television only showed their own victories.

When you wanted to search for a missing brother or father, whether captive, injured, or missing for any other reason, you had to intercept Iranian TV signals, which was impossible using local antennas that were all made with a particular shape.

So people started to construct their own antennas illegally in order to intercept the signals.

During that period I saw all kinds of twisted forms made from different materials. The funny thing is that when I went back after many years I found that one of those strange forms had made its way to becoming the only form of antenna being mass produced. It became official.

Unfaithful

My father worked for nearly all of the regimes in Iraq as a propaganda calligrapher. He never had a political orientation. Each time an event or reform was about to happen in the government, he would receive an assignment in advance, and the banners would then be hung on the streets of Sulaymaniyah. He delivered them without delay.

Sometimes I had the feeling he was holding the brush and the banners were moving under his brush.

One day, in early 1991, the banners turned from Arabic into Kurdish. That’s when we realized the Kurdish rebellion had taken over the northern part of the country.

Refer with Your Pinky, Not Your Index

During the Iran-Iraq War there were many indirect codes to be deciphered. Among them were the messages sent by the Iranian army to Iraqis.

As Iraq was a secular state, the army was well trained to be systematically ruthless and have no mercy for the enemy. The Iraqi military would randomly attack, firing missiles arbitrarily into different neighborhoods as a way of maximizing civilian causalities and causing terror.

On the contrary, Iran, as a religious state, had more merciful tactics. The Iranian military would focus their attacks on a single location over a period of time at regular intervals.

For example, they would fire a single missile into an area, and then take a short break to leave time for people to flee or take cover. Then the bombardment, scheduled routinely for a certain time of day, would be concentrated in a specific area of about one square kilometer. After a few weeks they would change the target to another neighborhood. This was a form of communication between the Iranian army and the Iraqi people.

I found another use of form without intent to harm when talking to workers who removed mines in Iraq. They would very often find mines that were buried by the Iranian military, but that were never armed to detonate.

For a Few Socks of Marbles

I grew up in different neighborhoods, Arab and Kurdish ones. Until I was nine I lived in an Arab neighborhood. The people who lived there were sent from the south to the north of Iraq as part of their service in the army.

I was always the black sheep there—they use to call me a Kurd and meant it as a form of insult. They could tell I was a Kurd because of my accent.

When I turned ten, we moved to a Kurdish neighborhood.

I was the only one in the neighborhood who didn’t wear the Kurdish shirwal (the traditional wide trouser). Now my biggest fear was to be called an Arab because of my Arabic accent when speaking Kurdish. It didn’t take long before they understood what I was afraid of, and soon they started calling me an Arab as a form of insult. I was marginalized and excluded again. For a child, it was really very hard.

Children play games according to seasons. For example, in autumn we used to play with kites because of the wind. Then, when the summer came, we played with marbles. Marbles and cowboy card collections from bubble gum packages were very popular among children. There were children who had many of them and who were quite well known even beyond their own neighborhoods. There were children who came to play and gamble from far away and they sometimes lost thousands of cowboy cards. The same happened with marbles. There were children who had ten socks full of marbles—it was like becoming a millionaire when you filled your first sock!

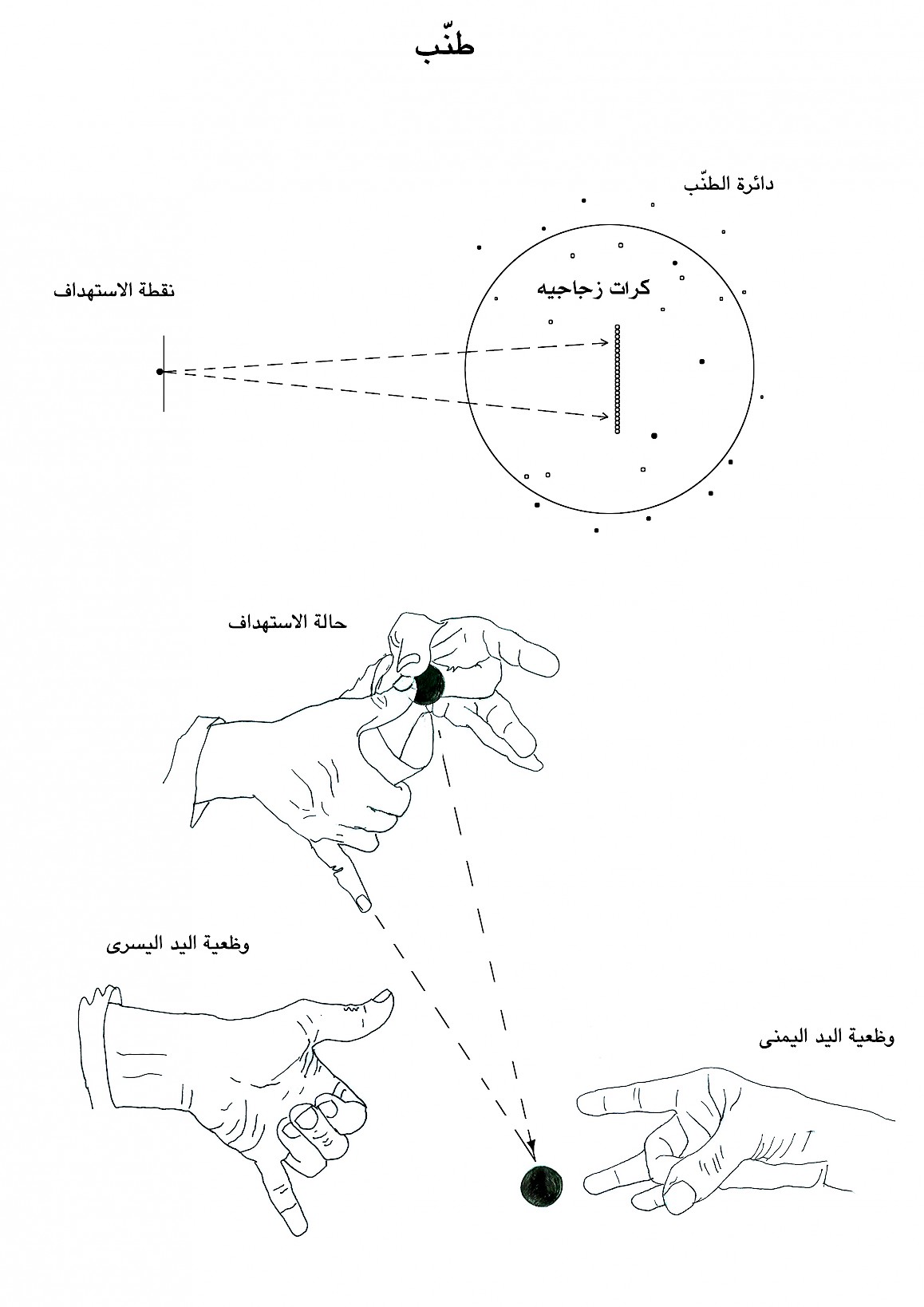

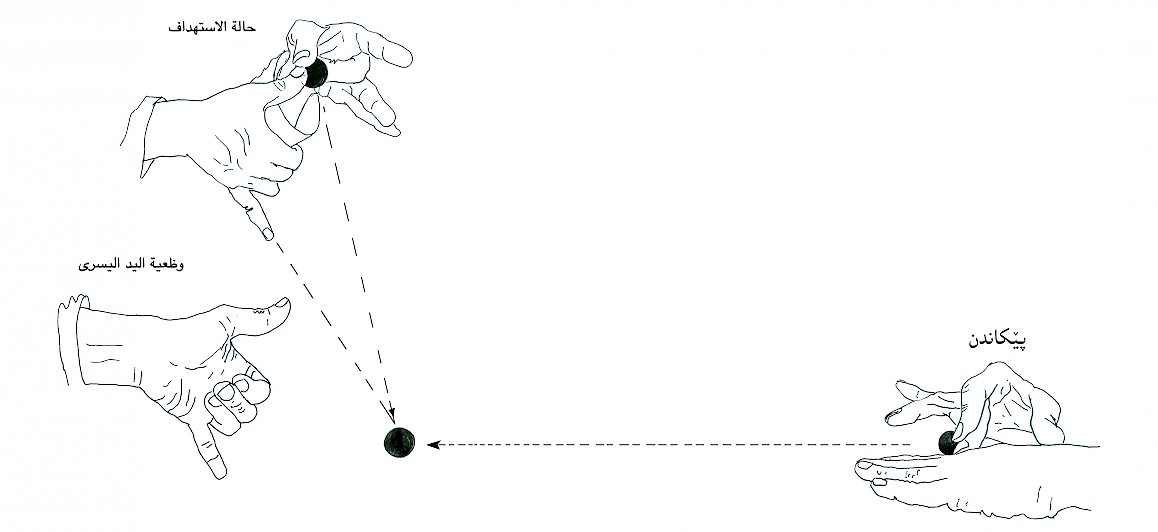

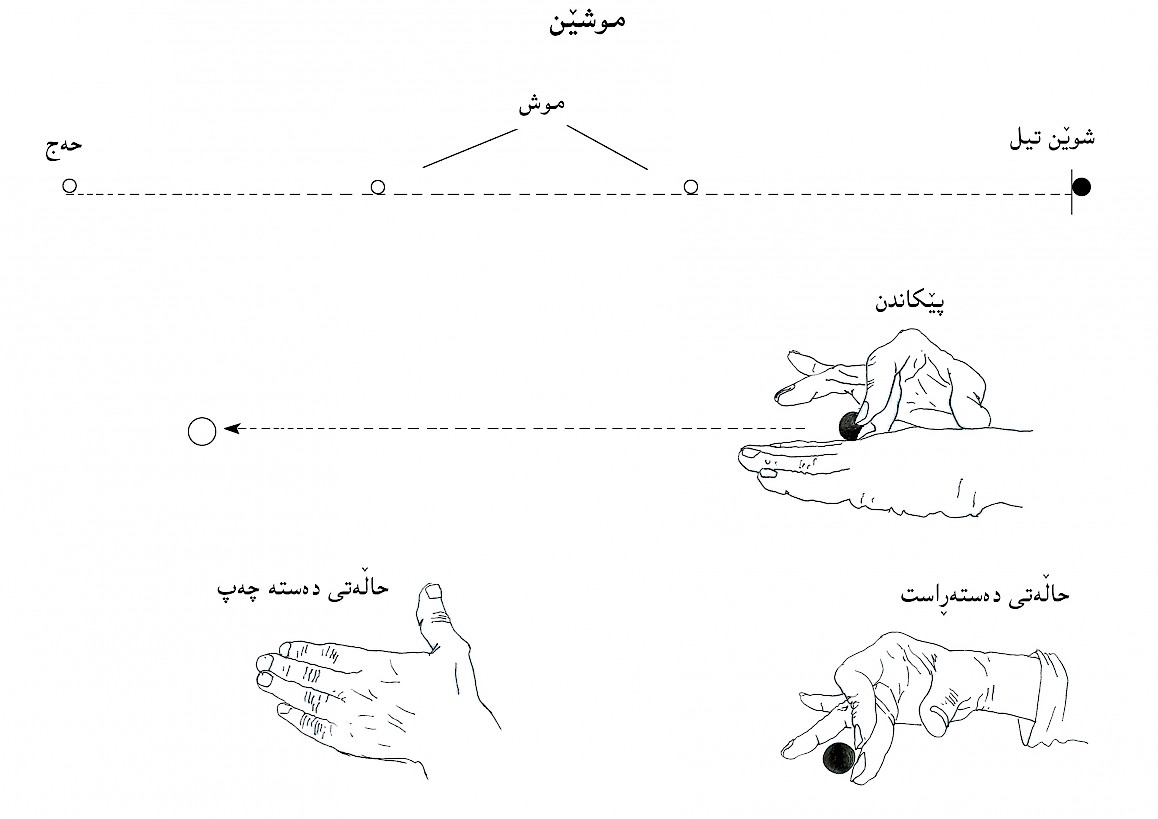

It was at that time that I started using what I had learned from the Arab style of marble playing. The Kurdish children in the neighborhood were playing the Kurdish way, using a horizontal hand position, which made it hard to hit the target when stones and small hills were in the way. They were playing a Kurdish marble game called mushien. This game was very complicated and had lots of rules. In some cases, for example, you were not allowed to hit the last marble, which was called “Hajj” (the pilgrimage to Mecca). There were many other regulations which didn’t make one feel free, and which usually won or lost only a few marbles at a time. On top of that, the most important marble was made from stone by the children themselves. Sometimes it took them months using a small hammer and a piece of paper to give the stone the perfect round shape.

I told them about my new game, called tannab. Tannab was much easier and had almost no restrictions at all, but the stakes were much higher; you could lose, for example, up to five marbles, and you could win up to twenty-five. The other boys were quite seduced by the game’s freedom and profitability. So we started playing. With the vertical hand position that I learned from the Arab neighborhood, I managed to bankrupt the whole street. Then afterwards I sold the marbles back to them. It was the beginning of the Eighties. I remember earning one dinar, which I gave to my mother to buy me a pair of Kurdish shirwal.

From then on I was accepted as one of them and no one called me an Arab again.

A View from Above

In the last four decades, many people have come from Iraq as refugees. In 1991, a division was created between northern Iraq (Kurdistan) and the rest of Iraq. The UN considers Kurdistan a safe zone. As a refugee you have to come from the unsafe zone, or at least prove that you do, in order to qualify as a refugee.

During the interview for refugee status, an official checks to see whether you really come from the unsafe zone. He asks about small details of the city you claim to come from, and compares your answers to a map to confirm that your answers correspond to it. If you cannot prove that you come from the unsafe zone, you are sent back to your country.

Many people have difficulty proving that they come from the unsafe zone, even if they really come from there.

Here is a story about someone who we can call M.

M tried to apply for asylum in one of the Schengen countries—let’s call the country “X.” He was not aware that the city he came from was in the safe zone, according to the UN. He waited five years for a positive answer from country X, but unfortunately he got one negative answer after another, until he received the final rejection from X and was set to be deported back to his country. Back then, his country was still ruled by a dictator. As a deserter from the army, returning to his country was the worst ending he could imagine. After a while he managed to cross the border of X without legal papers and enter another country—let’s call it XX—to apply for refugee status again. From that moment he was a new person.

Before going for the interview, he spent weeks with people from a town in the unsafe zone. Let’s call that town J. During this period he started to draw a map of J, which he had never visited before. He wanted to know every corner of it—the names of all the streets, the schools, the major buildings, and even the minor buildings. The people from J taught him everything and helped him draw the map of their town, all the while asking him questions to confirm that he had mastered everything about J.

When M finally had his refugee interview, the official was quite surprised, even impressed. He asked M questions about the geography of the town, and compared M’s answers to a map. M’s answers demonstrated knowledge of J as it was seen from above.

It took only twenty minutes for the official to grant M refugee status. Meanwhile, thousands of people who were actually from J and other cities in the unsafe zone waited as long as ten to fifteen years for the same thing, because their answers only demonstrated knowledge of their towns from the ground.

Flamenco Guitar Lesson with Paco Peña and Tony Blair

I have always been interested in two different modes of thinking in music. The first is what we have in the East, the Middle East, and Africa, which is melody-based music, in which the harmonic intervals are blindly related to each other in a horizontal way. The second is found in Western music, which comes from Christianity, and which has intervals that are related to each other vertically, like erected physical spaces.

One day I decided to apply to study with Paco Peña, a London-based flamenco guitar legend. I still don’t know why he accepted me, as I was a visual artist with only nine months of private guitar lessons.

During my lessons with him I discovered something. Paco is a very good friend of Tony Blair, and he has been teaching Blair how to play flamenco guitar for twenty years. Tony Blair is a flamenco guitarist.

In 2010, I approached Paco and asked him whether he would be interested in giving a lesson to both Tony and me together. He liked the idea, but said, “You have to convince Tony yourself.”

With the help of a former minister of culture in the UK, we approached Tony. But in the end, Tony didn’t accept the invitation; his assistant wrote that he was very busy with the peace process in Israel.

But I hope he will accept when we ask him again, as I read that he resigned from the peace process negotiations.

×

“A View from Above” and “Flamenco Guitar Lesson with Paco Peña and Tony Blair” were presented as part of Notes from an Extellectual, a performance by Hiwa K, with Carmen Amor and Adam Szymczyk. The performance took place in Kassel on July 18, 2015 as the closing event of the conference “documenta 1997–2017: Expanding Thought-Collectives.” Thanks to Aneta Szylak, Jason Waite, and Francesca Recchia for editing parts of these stories.