— Cosmic Anxiety: The Russian Case

During the period of modernity we grew accustomed to an understanding of human beings as determined by the social milieu in which they live, as knots in information networks, as organisms dependent on their environment. In the times of globalization we have learned that we are dependent on everything that happens around the globe—politically, economically, ecologically. But the Earth is not isolated in the cosmos. It depends on the processes that take place in cosmic space—in dark matter, waves and particles, stars exploding, and galaxies collapsing. And the fate of mankind also depends on these cosmic processes because all these cosmic waves and particles pass through human bodies. And the position of the Earth in the cosmic whole determines the conditions under which its living organisms survive on its surface.

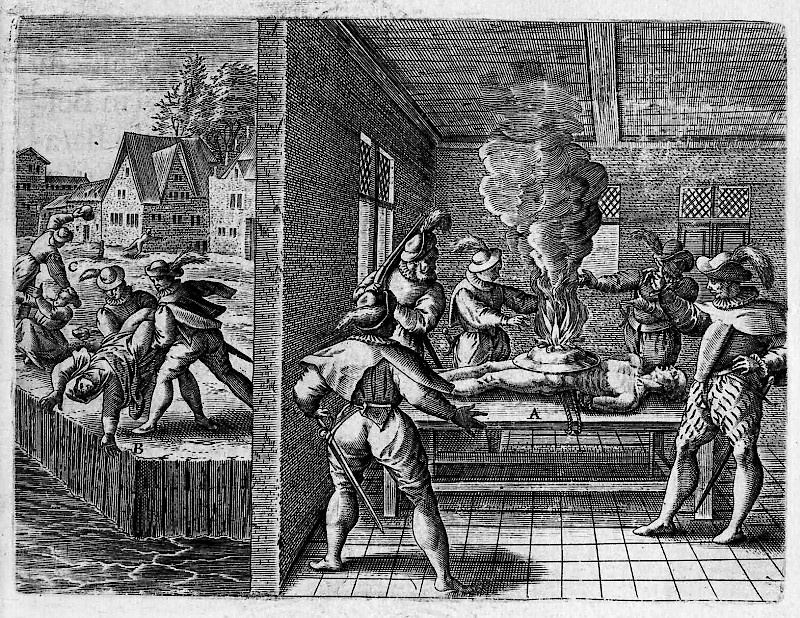

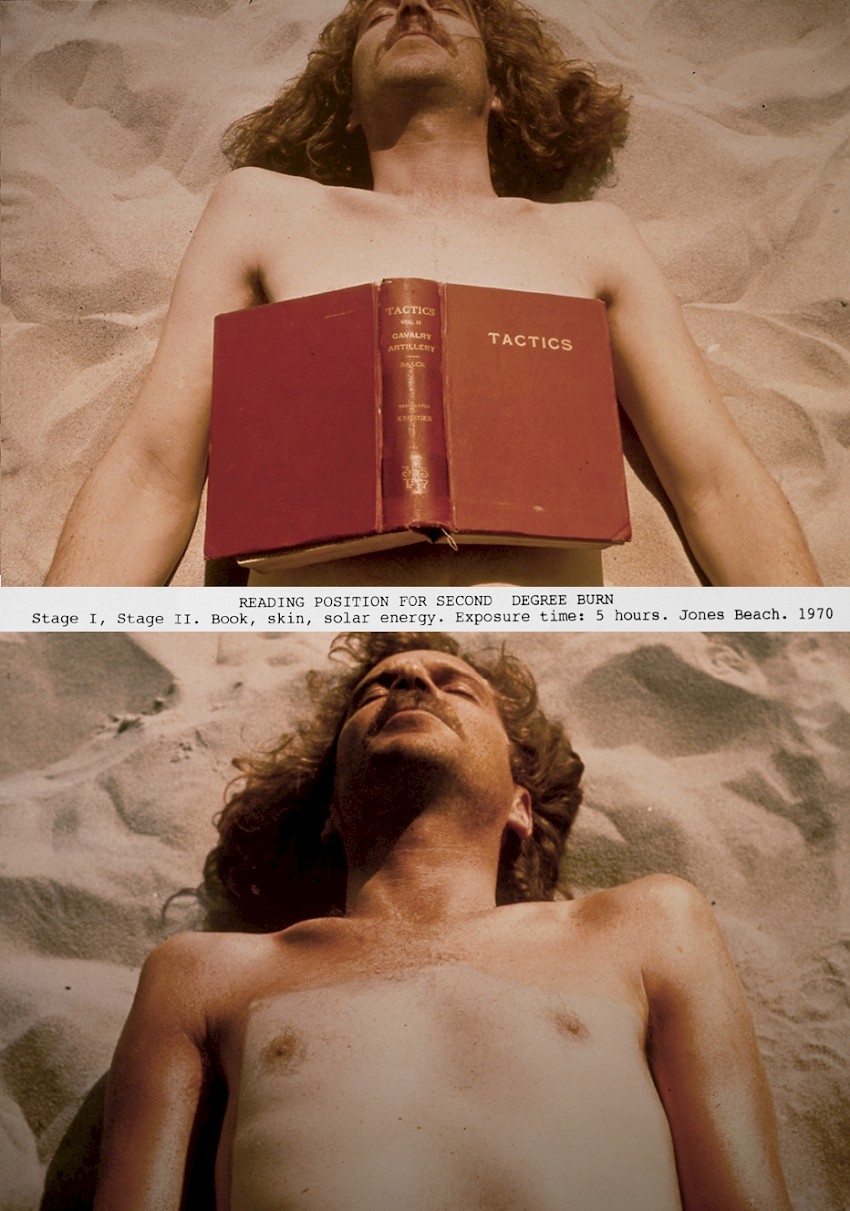

This dependence of mankind on cosmic events that are uncontrollable and even unknown is the source of a specifically modern anxiety. One can call it a cosmic anxiety: the anxiety of being a part of the cosmos—and of not being able to control it. Not accidentally, our contemporary mass culture is obsessed with visions of asteroids coming from black cosmic space and destroying the Earth. But this anxiety also has more subtle forms. One can cite Georges Bataille’s theory of the “accursed share,” for instance.1 Georges Bataille. Accursed Share: An Essay on General Economy, vol. 1 (New York: Zone Books, 1988). According to it, the sun always sends more energy to the Earth than the Earth, together with the organisms living on its surface, can absorb. After all efforts to use this energy for the production of goods and raising the living standard of the population, there remains a non-absorbed, unused remainder of solar energy. The rest of this energy is necessarily destructive—it can be spent only through violence and war. Or, at least, through ecstatic festivals and sexual orgies that channel and absorb this remainder of energy through less dangerous activities. In this way, human culture and politics are also determined by cosmic energies—forever shifting between order and disorder.

Friedrich Nietzsche described our material world, of which the human being is only a part, as the place of an eternal battle between Apollonian and Dionysian forces or, in other words, between cosmos and chaos. However, even if this battle is understood by Nietzsche as never ending, as always restoring the cosmos after being consumed by chaos, the Nietzschean vision offers a weak consolation to a humankind gripped by cosmic anxiety. Indeed, periodical restoration of the cosmic order does not guarantee the restoration of humankind as a small part of this order. Thus, only different ways of reacting to the battle between cosmos and chaos are possible: the ecstatic embracing of chaos or an attempt to control the cosmos and secure its victory over chaos.

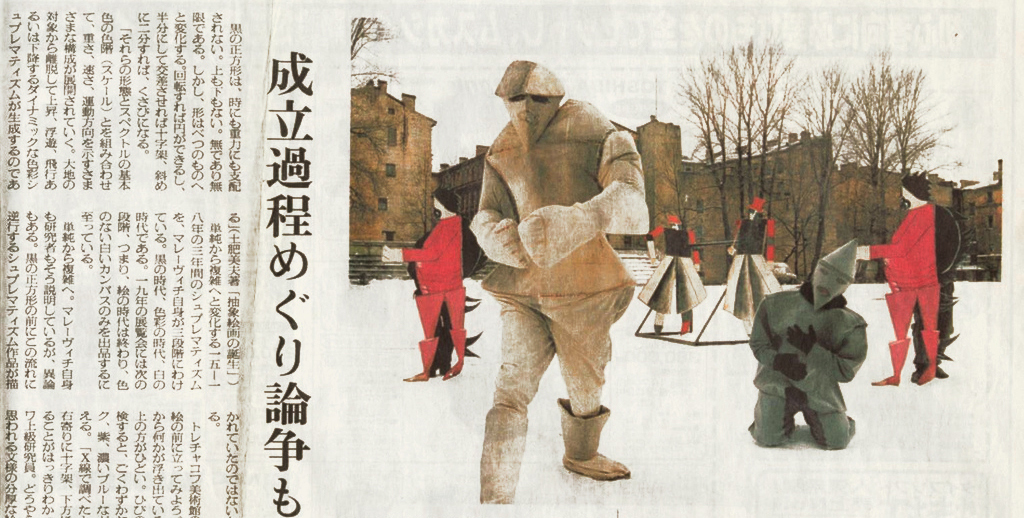

Both projects were formulated by Russian thinkers, poets, and artists at the end of the nineteenth and the beginning of twentieth centuries as Russia stood on the threshold of the revolution that plunged the whole country into total chaos. Many writers and artists invoked the coming of chaos—most famously the authors of the mystery-opera Victory over the Sun. The most prominent members of the Russian avant-garde movement of the time participated in its production: Kazimir Malevich, Velimir Khlebnikov, Aleksei Kruchenykh, and Mikhail Matyushin.2 Victory over the Sun, ed. Patricia Railing, trans. Evgeny Steiner. 2 vols. (London: Artists.Bookworks, 2009). The opera celebrated the extinction of the sun and the descent of cosmos into chaos, symbolized by the black square that Malevich painted for the first time as part of the scenography for the opera.

The reaction of the so-called Russian cosmists to Nietzschean radical atheism was different and in many ways similar to Marx’s reaction to the atheism of the French Enlightenment, or that of Feuerbach’s.3 George M. Young, The Russian Cosmists: The Esoteric Futurism of Nikolai Fedorov and His Followers (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 2012). Traditional atheism rejected Christianity as a false promise to secure the survival and even immortality of mankind. Man was persuaded to accept his finiteness, mortality, and incapacity to control his own fate. Marx was also an atheist, but he did not want to reject the Christian promise. Rather, he wanted to realize this promise by means of the communist society that would be able to take the fate of Earth in its hands instead of relying on divine grace. The Christian promise is reinterpreted here as a promise of the victory of the communist cosmos over capitalist chaos achieved by means of secular politics and technology.

The Russian cosmists inherited and radicalized this Marxist shift from divine grace to secular technology. However, there is one essential difference between the traditional Marxist project and the cosmist project. Marxism does not raise the problem of immortality: the communist “paradise on Earth” that is supposed to be achieved through the combination of revolutionary struggle and creative work is understood as a realization of harmony between man and nature—a harmony that secures human happiness in the framework of “human nature” to which the inevitability of “natural death” also belongs. In this sense the classical Marxist version of communism fits into the framework of biopolitical power as described by Michel Foucault.

Indeed, according to Foucault, the modern state functions primarily as a “biopower” whose justification is that it secures the survival of the human species. The survival of the individual remains, of course, not guaranteed. The “natural” death of any given individual is passively accepted by the state as an unavoidable event and is thus treated as a private matter for this individual. The death of an individual is thus the insurmountable limit of modern biopower. And this limit is accepted by a modern state that respects the private sphere of natural death. This limit was, by the way, not even questioned by Foucault himself.

But what would happen if biopower were to radicalize its claim on power and combat not only collective death but also individual, “natural” death—with the ultimate goal of eliminating it entirely? Admittedly, this kind of demand sounds utopian, and indeed it is. But this very demand was formulated by many Russian authors before and after the October Revolution. This radicalized demand of an intensified biopower contributed to a justification for the power of the Soviet state. Biopolitical utopias reconciled much larger circles of Russian intellectuals and artists with Soviet power than Marxism alone ever managed, especially because these utopias had, unlike Western Marxism, a genuinely Russian origin—namely, the work of Nikolai Fedorov.

The “Philosophy of the Common Task” that Fedorov developed in the late nineteenth century may have met with little public attention during his lifetime, but it held the attention of illustrious readers like Lev Tolstoi, Fedor Dostoevskii, and Vladimir Solov’ev, who were fascinated and influenced by Fedorov’s project.4 Nikolai Fedorovich Fedorov, What is Man Created For?: The Philosophy of the Common Task (London: Honeyglen Publishing/L’Age d’Homme, 1990). After the philosopher’s death in 1903, his work gained ever-increasing currency, although in essence it remained limited to a Russian readership. The project of the common task, in summary, consists in the creation of the technological, social, and political conditions under which it would be possible to resurrect by technological, artificial means all the people who have ever lived. Fedorov understood his project as the realization of the Christian promise of resurrection and immortality through technological means. Indeed, Fedorov no longer believed in the immortality of the soul existing independently of the body. In his view, physical, material existence was the only possible form of existence. And Fedorov believed just as unshakably in technology: because everything is material, physical, everything is technically manipulable. Above all, however, Fedorov believed in the power of social organization: in that sense he was a socialist through and through. Fedorov took seriously the promise of the emerging biopower—that is, the promise from the state that it would concern itself with life as such, and he demanded of this power that it think its promise through to the end and fulfill it.

Fedorov was reacting to an internal contradiction in the socialist theories of the nineteenth century that understood themselves as theories of progress. And that meant that future generations would enjoy socialist justice only at the price of a cynical acceptance of an outrageous historical injustice: the exclusion of all previous generations from the realm of the socialist utopia. Socialism thus functioned as an exploitation of the dead in favor of the living—and as an exploitation of those alive today in favor of those who would live later. But is it possible to think of technology in terms that are different from the terms of historical progress?

Fedorov believed that such a technology directed towards the past was possible—and, actually, it already exists. It is art technology and, especially, technology used by art museums. The museum does not punish the obsoleteness of the museum items by removing and destroying them. Thus the museum is fundamentally at odds with progress. Progress consists in replacing old things with new things. The museum, by contrast, is a machine for making things last, making them immortal. Because each human being is also one body among other bodies, one thing among other things, humans can also be blessed with the immortality of the museum. The Christian immortality of the soul is replaced here by the immortality of things, or of the body in the museum. And divine grace is replaced by curatorial decisions and the technology of museum preservation.

According to Fedorov, art uses technology with the goal of preserving living beings. There is no progress in art. Art does not wait for a better society of the future to come—it immortalizes here and now. Human beings can be interpreted as readymades—as potential artworks. All of the people living and all the people who have ever lived must rise from the dead as artworks and be preserved in museums. Technology as a whole must become the technology of art. And the state must become the museum of its population. Just as the museum’s administration is responsible not only for the general holdings of its collection but also for the intact state of every work of art, making certain that the individual artworks are subjected to conservation and restoration when they threaten to decay, so should the state bear responsibility for the resurrection and continued life of every individual person. The state can no longer permit itself to allow individuals to die privately or the dead to rest peacefully in their graves. Death’s limits must be overcome by the state. Biopower must become total.

This totality is achieved by equating art and politics, life and technology, and state and museum. The overcoming of the boundaries between life and art is not a matter of introducing art into life but is rather a radical museumification of life—life can and should attain the privilege of immortality in a museum. By means of unifying living space and museum space, such biopower extends itself infinitely: it becomes the organized technology of eternal life. Such a total biopower is, of course, no longer “democratic”: no one expects the artworks that are preserved in a museum collection to democratically elect the museum curator who will care for them. As soon as human beings become radically modern—that is, as soon as they are understood as bodies among other bodies, things among other things—they must accept that state-organized technology will treat them accordingly. This acceptance has a crucial precondition, however: the explicit goal for a new power must be eternal life here on Earth for everyone. Only then the state ceases to be a partial, limited biopower of the sort described by Foucault and becomes a total biopower.

×