— The Art of Cooking: A Dialogue Between Julia Child and Craig Claiborne

Julia Child: Craig, my dear, I’ve been thinking. We all know that cooking is an art. But I wonder: How did it get to be one? After all, most of what we think of as art hangs on the wall or sits out in a courtyard ...

Craig Claiborne: Well Julia, I know what you mean. Yet obviously there are many kinds of art that don’t do that. Aside from cooking, we have music, the theater, dance—

Julia Child: Yes, Craig. But those haven’t any use: I mean, how serious are we about cooking as art? Cooking does tend to get used up rather quickly, you know.

Craig Claiborne: Yes, cooking is an ephemeral art; the painter, the sculptor, the musician may create enduring works, but even the most talented chef knows that his masterpieces will quickly disappear. A bite or two, a little gulp, and a beautiful work of thought and life is no more.1Sybil (Bolitho) Ryall, in A Fiddle for Eighteen Pence, quoted in Craig Claiborne, Classic French Cooking (New York: Time-Life, 1970), 73.

Julia Child: I see. You’re talking of masterpieces and talent and beautiful work, but isn’t cooking primarily a matter of taste?

Craig Claiborne: Of course! But isn’t all art a matter of taste?

Julia Child: Yes! But are they the same kind of taste?

Craig Claiborne: Classic French cooking is a fine art, as surely as painting and sculpture are. Its great works, such as poularde à la Néva and filet de bœuf Richelieu, are masterpieces designed to enchant both the palate and the eye. And the classic French cuisine implies as well the careful planning of a menu to insure a felicitous blend of textures, colors, and flavors; it means sparkling crystal, gleaming silver, and immaculate napery. When all these come together, it is one of the glories of the civilized world.2 Claiborne, Classic French Cooking, 8.

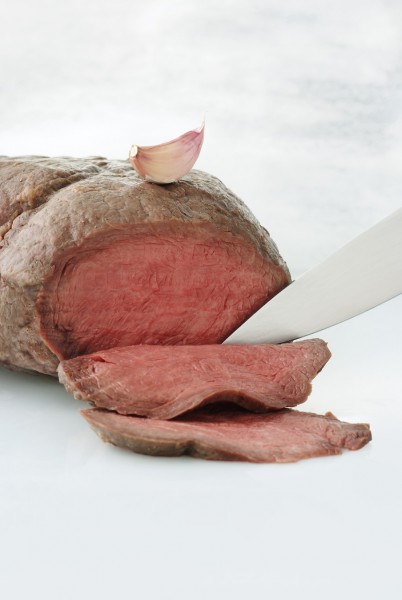

Julia Child: You’re right. You know, it has been the French who elevated cooking to an art—taking it seriously as art. And surely, in our time French cooking has come to be recognized as an art indeed. And no wonder. The French seem to look for the hidden flavor locked within a piece of meat in much the same way a sculptor looks for the shape within a block of wood or marble.3 Linda Wolfe, ed., McCall’s Introduction to French Cooking (New York: McCall, 1971).

Craig Claiborne: The French approach the food on their plates with an eye toward the visual, toward the arrangement of shapes and colors. And in the pot, the equivalent of the painter’s palette, they are concerned with the blends among foods, the delicate variations and shadings that can be obtained by increasing or decreasing certain ingredients, adding one flavor, subtracting another.4 Ibid.

Julia Child: Yes! Louisette, Simone, and I dedicated our book to La Belle France, whose peasants, fishermen, housewives, and princes—not to mention her chefs—through generations of inventive and loving concentration have created one of the world’s great arts.5 Julia Child, Louisette Bertholle, and Simone Beck, Mastering the Art of French Cooking (New York: Knopf, 1967).

Craig Claiborne: Lovely sentiments. But of course the peasants, fishermen, and housewives can hardly be credited with developing the high art of cooking, the true classic cuisine. Nothing that is vulgar or earthy has a place in the classic repertory. Many excellent dishes fail to qualify as classics because they lack the necessary elegance.6 Claiborne, Classic French Cooking. What you say about the chefs and princes in your dedication, if I may, is somewhat closer to the truth. The classic cuisine blossomed in the palaces and châteaux of pre-Revolutionary France, and it came to flower in the days of the great French chefs Carême and Escoffier.7 Ibid., 11.

Julia Child: I know! But ...

Craig Claiborne: My dear, I’m making a point. High art may grow out of the arts of the people, but it does not spring directly from them. Forgive me for observing that you ladies are too accepting, not rigorous enough in what you allow as art. If I recall correctly, it was one of your sex who attempted to lionize French provincial cooking over the classic cuisine. It’s much like preferring quilts to Picasso. The woman’s English ancestry may be at fault here—the English tend to be egregiously barbaric about their food, but often surprisingly folksy and sentimental about the laboring classes from the pastoral past. But high art requires a dedication they, through circumstance if nothing else, must lack. There are many outstanding regional dishes that do not make the grade as classics.

Julia Child: In my opinion, cooking is not a particularly difficult art, and the more you cook and learn about cooking, the more sense it makes. But like any art, it requires practice and experience.8 Child, Bertholle, and Beck, Mastering the Art of French Cooking, Foreword, viii.

Craig Claiborne: You too are failing to make the necessary, the crucial, distinction between low art and high art.9 Claiborne, Classic French Cooking.After all, perfection is the goal of classic French cooking, and this cuisine is more demanding and more precise than any other. It has its own logic, its own elaborate structure, its own techniques, procedures, and caveats.10 Ibid.

Julia Child: As I see it, the French people as a whole are responsible for the great cookery of France (though lately, I confess, there has been slippage). All the great chefs came from the provinces. Even the great sauces and stocks are descended from the peasant soups, for example. Why, even Louis Diat, the great chef at the Ritz, traces his creation, vichyssoise, to the soups of his native Brittany, where soup was a staple and was eaten three times a day.

Craig Claiborne: Julia, dear, it doesn’t matter so much where artists, and chefs, come from. It’s where they get to, what they make of themselves, that really matters. It was not little Louis Diat the Breton peasant but Louis Diat the great chef who created the soup. The incomparable Carême is the shining example of the man who dragged himself up from the gutter. The sixteenth child of an improvident stonemason, he began life in a Paris slum and by hard work, study, and rigor, made himself a great artist. He stayed up night after night studying the designs he’d made from classical reproductions in the Bibliothèque Royale, to learn about art.

Julia Child: Well! You began with painting and sculpture, and now we arrive at drawings and replicas of classical structures. Just what kind of art is cooking, after all? Let’s remember how the Executive Committee of the famous Salon d’Automne, at a meeting at the Grand Palais, on June 7, 1923, adopted Austin de Croze’s proposal to create a special section of the salon devoted to the gastronomy of the French provinces, passing a resolution by which “Gastronomy, including cooking and cookery, is officially recognized to be an art, the Ninth Art.”11 Austin de Croze, What to Eat and Drink in France (London: Frederick Warne & Co., 1931).

![In the archives of the New York Public Library one can find evidence of summer nights in early twentieth-century Manhattan, featuring wealthy patrons “dining in the extremely attractive surroundings of the roof garden restaurant of the Ritz-Carlton Hotel, New York, 1918, in which dancing [was] enjoyed during the dinner hour and evening.”](/site/assets/files/1086/3__07_rosler--vichissoise_nypl_digitalcollections_510d47e1-27f4-a3d9-e040-e00a18064a99_001_w.jpg)

Craig Claiborne: What did they consider the other eight to be?

Julia Child: Why, they were “Architecture, Sculpture, Painting, Engraving, Music and Dancing, Literature and Poetry, the Cinema, and Fashion.”12 Ibid.

Craig Claiborne: Oh, fashion. To be sure.

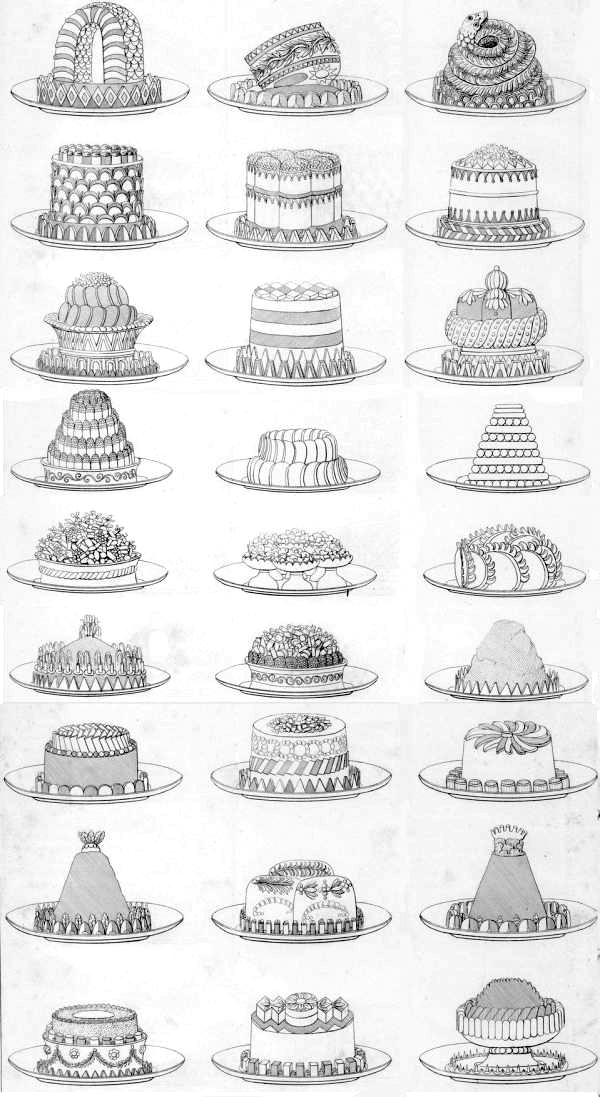

Julia Child: Carême, on the other hand, wrote that “the fine arts are five in number, to wit: painting, sculpture, poetry, music, architecture—whose main branch is confectionery.”13 Prosper Montagné, Alfred Gottschalk, Auguste Escoffier, and Philéas Gilbert, Larousse Gastronomique (Paris: Montrouge, 1949), 186.It was architecture that Carême, the stonemason’s son, was studying in the library. He started as an apprentice to a fine pastry maker, as you know, and built replicas of classical temples and fountains, forts, helmets, and even ruins, in pastry. Now, we may not ordinarily consider cooking as architecture, but Carême made models out of foodstuffs and treated his banquets as architecture. Architecture is surely a grand art—it makes a lavish display. It is solid, and visually exciting, even inspiring—and it has an air of permanence about it. Sculpture is, after all, reductive of materials rather than additive, as architecture and cooking are, and it is not as grand or self-referential as architecture. Architecture invites habitation, drawing the diner inside, as it were, unlike painting, which invokes the eye more than the body. The diner inhabits the creation, but then the creation, in the form of food, inhabits the diner.

Craig Claiborne: Architecture was generally conceded to be the grandest of the arts in the eighteenth century, when Carême was born. He did his cooking for the great houses, before and after the Revolution. Interest in classicism was very high, and as a reflection of his classical concerns, Carême took great care with principles of balance and order. His was a noble spirit.

Julia Child: Yes, he loved glory above all else and looked upon his profession as a sacred trust… Money meant nothing to him. His art alone was important. He prized nothing but the glory of his profession. His very conception of culinary art is in tune with the grandeur of his character.14 Montagné, Larousse Gastronomique, 212.

Craig Claiborne: He was a lofty and dedicated artist. But he didn’t invent the idea of re-creating, in food, buildings, castles, ruins, and so on. The entire Western world produced such re-creations from the Middle Ages onward. In Italy they were called trionfi di tavola, in France pièces montées, or set pieces, in England “subtleties.”

Julia Child: But Craig, are these art?

Craig Claiborne: Before Carême’s day, pièces montées had been grandiose and vulgar almost beyond belief.15 Claiborne, Classic French Cooking, 75.

Julia Child: Johan Huizinga dubs the entremets of fifteenth-century Burgundian France “exhibits of almost incredible bad taste.”16 Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages, 250.These entremets, related to the set pieces in style and origin, sometimes took the form of gigantic pies enclosing complete orchestras, full-rigged vessels, castles, monkeys and whales, giants and dwarfs, and all the boring absurdities of allegory.17 Ibid.He too considers the question whether they were art. But just calling something vulgar or maligning its taste doesn’t answer the question whether it is art. Using taste as the absolute standard of art could be taken to imply that taste is something timeless and independent of any single individual. Conversely, it might indicate that the meaning of art has a built-in value judgment and that what qualifies as art depends on what suits each person’s taste—each individual would decide what is art on the basis of what each fancies. If we like it, it’s art; if not, it’s not art. Voilà!

Craig Claiborne: Let’s not pull this pie out of the oven too quickly, my dear. There are other possibilities. For example, we might maintain that taste is a quality that inheres in refined, interested, and educated persons of any age, and that although the objects of good taste might not be universal to all times and places, still, they have a certain something that is recognizable to persons of taste of whatever era or locale. I think there is a notion of bad art—works that show a fair degree of skill and may even present appropriate subjects. But—

Julia Child: Appropriate subjects?

Craig Claiborne: Surely that enters in, don’t you agree? Pornography, for example, isn’t really considered art, nor does it cover workaday subjects, I imagine.

Julia Child: I think many people would concede that much of what is considered art is at least somewhat pornographic—Rubens or Titian or Boucher or Fragonard’s boudoir paintings, perhaps ... Some of Ingres or Delacroix, Courbet, and Manet, Picabia, and of course many late Victorian sentimental ...

Craig Claiborne: All that might now be dubbed soft-core or merely, well, racy. But I suppose there is inevitably some sort of value judgment involved in a definition of art.

Julia Child: We expect art to strike us as exceptional, not common, as you’ve suggested yourself. We’ve used the word “vulgar,” which does mean both “common” and “in bad taste.” I find that a trifle odd when applied to cooking.

Craig Claiborne: Why?

Julia Child: Well, when we say, “The Viennese have elevated pastry-making to an art,” we’re making a sweeping statement about the Viennese.

Craig Claiborne: Yes, but surely we don’t mean all Viennese people make artistic pastry, and we don’t mean that all Viennese pastry makers make artistic pastry. We are describing a cultural achievement, a civic one.

Julia Child: All right, then. Let’s leave out sweeping generalizations, especially ones based on tribal identity. Could we rather say that art is the best of what is produced in a certain line of endeavor, opening it to anyone, anywhere? I’m not altogether comfortable with that idea, though, because in cooking, pleasing the taste is the final criterion, so we would have to exclude a lot of endeavors. Would one accept superbly prepared insects as food art if we abhorred insects or loathed the very idea of eating them?

Let’s keep on with the question of representation—but let’s get down to earth, onto architectural terrain. So, would we accept superbly prepared insects as food art if we abhorred insects or loathed the very idea of eating them? To return to the architectural, would we allow a Carême pastry formed to represent a Greek ruin to be considered as art? And wouldn’t we already have to believe that cooking could somehow be like architecture? I began by wondering why Carême’s architectural pastries are accepted as art, whereas those made in previous eras were not. That would seem to be just a matter of our taste working retrospectively, but Huizinga would object, and remind us that the medieval set pieces were unworthy of being considered as art because they do not embody any spiritual values and because they were made in a period that did not have a valid concept of art at all.

Craig Claiborne: Oh?

Julia Child: For us, art is somehow separate from and perhaps even above the rest of life. They didn’t think that way in the medieval world. Art played a more integrated role—glorification, decoration, and simple amusement. Huizinga asks: What was the artistic execution worth? What people looked for most was extravagance and huge dimensions. The tower of Gorcum represented on the table of the banquet of Bruges in 1468 was forty-six feet high.18 Huizinga, The Waning of the Middle Ages.Huizinga, while he hates all this, nevertheless reminds us that the patrons of these spectacles were also the patrons of the van Eycks and of Rogier van der Weyden. For him the ultimate affront is that it was the painters themselves who designed these show pieces.19 Ibid., 253.I suppose, then, we have to count restraint, separation, and seriousness in our definition of art. Even in cookery, of course.

×

In approximately 1973–1975, in the midst of a body of works on food, taste, labor, women, and imperialism, Martha Rosler wrote “The Art of Cooking,” a dialogue between Julia Child, the pioneer television chef bringing French cooking to American audiences, and the New York Times’s noted restaurant critic Craig Claiborne. The imaginary conversation is substantially composed of quotations from cookbooks of the era, redirected toward a discussion of the role of taste in art. This is a short excerpt of the book-length dialogue, to be published by e-flux in 2016.