— Men of Bronze, Homes of Concrete

Here

Men are made of bronze.

Homes are made of concrete.

The city is designed as a 1 km circle,

with rings of functional structures

along the inside of its walls.

It was not built before two astrologers

advised on the date and time.

July 30, 762 at 1:57 p.m.

They say it is the revealing of the sky …

If people listen to prophets,

No catastrophic ordeal sends its loud laughter …

And the shabby odious myth rarely could be related …

Centuries after centuries carried the bitter poison …

Its bitter echo sparkles as if it were a furious fire …

Can this intolerant passion stop with the touch of a cool hand? 1 Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, “Myths” (1950), poem translated from Arabic by Mohammad Mahmud Ahmad.

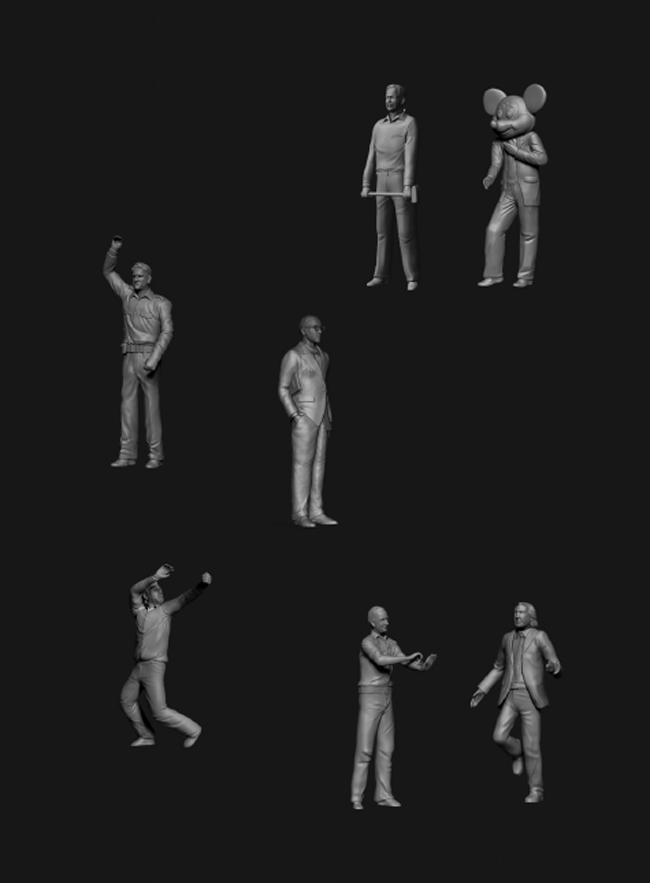

This man

who happened to be a difficult person sometimes,

and who sought to be recognized as an artist,

is Le Corbusier.

His name is linked to that of Saddam’s

in a gymnasium built in Baghdad,

though both men never really met.

Online is a photo of a black cover of the

“Saddam Hussein Gymnasium” pamphlet,

published by the Iraqi Tourism Board in the 1980s.

One can see from the spaces left between the words

that someone used a felt-tip pen

to remove Saddam’s name.

It happened in 2014 to a Wikipedia page created in 2008.

A user succeeded in renaming the page of

Saddam Hussein Gymnasium

to “Baghdad Gymnasium.”

A facsimile of a letter from Madhat Madhloom,

on a miniature desk of Le Corbusier in 1956.

“Dear Monsieur Le Corbusier,

I was delighted to meet you in Paris

Thank you for giving up so much of your time

to discuss the stadium project in Baghdad.

I am enclosing with this letter

two copies of the Scale of Charges

which you asked for as a guide to your fees.

It is normally accepted by the Government of my country

on works of this size to pay fees at customary English rates.” 2 FLC P4 2 22.

1957 in Baghdad,

a miniature of Le Corbusier asking

a miniature of Iraq’s Director of Physical Education nodding:

“A swimming pool with [artificial] waves?”

His arm is raised as if swimming the backstroke.

They have just discovered a mutual interest in water sports.

“There is no doubt that Le Corbusier is an exceptional architect,

but his services will certainly be expensive,

since they are greatly sought after …

there is no certainty that he is an expert in the building of stadia.

We might be able to arrange a meeting

to exchange views,

we would then be able to supplant Mr. Le Corbusier

and make progress in gaining acceptance for our bid.” 3 Nuno Grande, “Gulbenkian vs. Le Corbusier,” Jornal Arquitectos 250 (May–August 2014): 414–17.

On July 13, 1958, a confident Le Corbusier is pleased

but not surprised to receive a telegram

informing him that his design had been approved. 4 Mina Marefat, “Mise au Point for Le Corbusier’s Baghdad Stadium,” Docomomo 41 (September 2009): 30.

On July 14, 1958, a military coup overthrows Iraq’s monarchy.

A republic is announced.

Brigadier Abdel Karim Kassem is prime minister.

Miniature of Rifat Chadirji

leaving a hospital.

His visit to Kassem was to convince him

not to change the stadium’s location.

He showed him Baghdad’s new master plan by Doxiadis.

Miniature of Kassem coming out to the crowds

a blue line photoshopped between his fists,

one arm is raised and the other is near his belt:

“This is our future water canal that will link the Tigris to the Euphrates.”

The line looks like an arm support.

Kassem is recovering from a gunshot to his hand

that he received in a failed assassination attempt.

Sympathy for a bullet to cut open the depths of my heart,

With its constrictive ice,

To burn up the bones like in hell.

I wish I could run to support those struggling,

To tighten both my fists and slap fate. 5 Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, “The River and The Death,” poem translated from Arabic by Jamil Azeez Mohammad.

The Tigris and Euphrates also carry large quantities of salt.

These, too, are spread on the land by excessive irrigation and flooding.6 “Rivers and Drainage in Iraq,” Library of Congress Country Studies (US) →

Miniature of Abdel Karim Kassem receiving the news

that his face does not appear on the July Revolution Monument.

He is relaying the message [and a request]

to a miniature of Rifat Chadirji.

Miniature of Chadirji shaking his head

denying the request to a miniature of [a worried] Jawad Salim.

Chadirji and Salim are protecting [the future] of the monument,

by keeping it free from any depictions of rulers.

Miniature of Jawad Salim almost falling to his knees,

just like one of the hidden pieces in his mural.

He finishes the mural’s bronze parts,

but dies before it’s time to install it.

At the morgue, Khaled Rahhal is trying to make a mould of Salim’s face.

Miniature of Chadirji blocking Rahhal’s access

to the monument construction site.

To [further] protect it from view,

the bronze parts remain covered [with gypsum]

until the day Kassem arrives

for the monument’s inauguration.

Here, no miniature for Chadirji,

as he travels the day before.

Magazines reports:

people claim to have seen Kassem’s face on the moon,

and some saw it on an egg,

just after he was killed in a military coup in 1963.

Desirous eyes tempt themselves straying to the sky.

They looked about any hopeful way … 7 Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, “Myths.”

“We have followed with great interest

the recent political developments that took place in Iraq.

We would very much appreciate knowing the position

of your ministry in regards to this important project.

Very faithfully yours.” 8 Letter from Ph. Roulier and G. M. Presente to the Ministry of Public Works and Housing, Baghdad, dated April 2, 1963. FLC P4 7.

It is said that his regulations on oil killed the man

others say that it was the Nasserist Arab union promise

1963 is said to be a difficult year,

after all these mega events

and the recession.

There were no recreational facilities in Baghdad,

there were only martial laws, then nationalization,

of all banks and over thirty major Iraqi businesses in 1964.

To regain investors’ confidence,

the government pushed well-known individuals to have their own stake in the market.

There were no amusement parks in Baghdad,

until the founding stone of one was laid by Abdel Salam Aref in 1964.

President Aref,

who is said to be against executing Kassem

or airing his execution scenes on national TV,

has been an ever-smiling man.

He is keen on initiating and following up on development himself.

No new master plans for Baghdad in his time,

but many construction and infrastructure projects.

Miniature of Abdel Salam Aref in military dress

emerging from a dust cloud whipped up by his helicopter’s descent into a village.

One hand is gesturing

[to stop the cheering of the crowd, which has lasted for half an hour].

The other hand is folding the opposite arm’s sleeve.

His face signals [Let’s plan!]

to a miniature of Rifat Chadirji.

Le Corbusier drowns

the same year.

Welcoming words, speeches, journalists, and tribesmen

escort Aref to his Soviet-made helicopter

which will take off and soon spin out of control.

Hovering over palm groves and the Tigris,

Aref escapes the crash and jumps

but he falls at the dirt edge of the river,

and dies.

Miniatures of actors,

in blue collared shirts and overalls,

standing in a small boat in the middle of the Tigris.

Attentive, terrified, frozen,

one is almost crying,

while another is raising a sickle to an unknown danger hidden in Al-Ahwar.

“In the remote forgotten unknown land,

and under the pressure of the hard natural circumstances,

they rush on;

men like the stones,

like night,

like thunder …

And where lies the magic of the primitive world,

the mystery of its conditions,

also lies fear and hope and expectations.” 9 Iraqi Department of Cinema and Theater, “The Searchers,” Iraqi Feature Films, 97.

Of all the hazards of living in Iraq,

dealing with venomous snakes may be the least discussed.

Six species of dangerously venomous snakes are dangerous to Al-Ahwar natives.

The Baghdad Zoo opens in 1971.

Some books wrote: it is considered the largest zoo in the Middle East.

1973’s oil revenues gave Baghdad happiness like never before.

The seventies are considered the city’s golden age.

To Le Corbusier’s contractor, a lawyer from Baghdad writes:

“If Mr. Le Corbusier died without any bodily heir

and there was no competent evidence proving the existence of such heirs,

the Iraqi Government shall be the sole heir

and shall possess the amount of the deceased.” 10 Letter from Advocate A. R. Al-Saidi to Mr. Ph. Roulier, dated November 7, 1973. FLC P4 013.

Saddam is a rising star as the strong deputy of the president.

His surprise visits are aired on national TV;

he picks up phone calls to his office himself

to answer people’s requests,

that phone does not stop ringing.

Miniature of Saddam Hussein in 1980,

a young president attending Baghdad’s conferences on architecture.

He has preferences, even regarding small details like arches.

He sends notes to this effect to a miniature of Rifat Chadirji,

who is about to be released from prison.

Participate in a grand project preparing Baghdad

to host a Non-Aligned Movement summit in 1982!

The government spends more than $7 billion

to give Baghdad a facelift.

Freeways and wider streets across the city,

five-star hotels,

modern shopping centers,

high-rises,

and several new bridges.

The city is adorned with historical and modern monuments,

as well as pictures of the president.

The government spends 6.5 million dinars

to build the gymnasium,

in twenty-two months.

Miniature of Chadirji rushing

to the site of the Monument [to the Unknown Soldier].

He just learned of Saddam’s order to demolish it.

He takes a photo of himself near the rubble of the monument he built in 1959.

The site soon hosts Saddam’s statue

that is pulled down [in a possibly staged moment] in 2003.

Khaled Rahhal designs

a new Monument [to the Unknown Soldier] at another site.

I feel I have crossed the expanse

To a world of decay that responds not

To my cry

If I shake the branches

Only decay will drop from them

Stones

Stones—no fruit

Even the springs

are stones. 11 Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, “For I Am A Stranger,” poem translated from Arabic by Mohammad Mahmud Ahmad.

Answering to Saddam’s inquires

about how to identify the eras

to which historical sites belong,

archaeologists said:

“From the King’s stamp on the bricks.”

He “considered himself to be

the reincarnation of Nebuchadnezzar

and had the inscription

‘To King Nebuchadnezzar

in the reign of Saddam Hussein’

inscribed on bricks inserted into the walls of the ancient city of Babylon

during a reconstruction project.” 12 Michael L. Galaty and Charles Watkinson, Archeology Under Dictatorship (New York: Springer, 2004), 203.

On a wall, another mural

a miniature of Saddam Hussein [in military dress]

[humbly] receiving

a palm tree,

handed over by a miniature of [a mighty] Nebuchadnezzar.

A blue sky is behind them,

and below are scenes of desert battles

from different times.

Oh, when will you come back?

Will you know, I wonder, when daylight fades,

how much the fingers’ silence knows

about the flashes of the unseen

in life’s darkness?

Oh, let me have your fists.

They fall as snow falls,

no matter where I look,

as snow descends upon my palms

and falls headlong into my heart.

How often have I dreamed about those fists,

as two flowers growing by a stream

unfolding where my loneliness wanders, lost. 13 Badr Shakir al-Sayyab, “Day Has Gone,” poem translated by Adnan Haydar and Michael Beard.

Miniatures of a happy audience

celebrating New Year’s Eve 1990,

dancing to the music of Adel Ogla

at the Saddam Hussein Gymnasium.

Miniature of a man

wearing a Mickey Mouse costume

dancing on the [green] expanse

of the gymnasium’s basketball court.

Other men in other character costumes dancing too.

And a massive drawing

depicting Saddam in traditional garb,

with a big smile,

appears on the wall in the background.

The man dressed as Mickey climbs the stairs

to the officials’ podium,

to [respectfully] shake the hand

of a ministry representative.

Sometimes, his face covers

the entire screen

in the video footage that was found later.

“When I lead my army against Baghdad in anger,

whether you hide in heaven or on earth,

I will bring you down from the spinning spheres;

I will toss you in the air like a lion.

I will leave no one alive in your realm;

I will burn your city, your land, yourself.

If you wish to spare yourself and your venerable family,

give heed to my advice with the ear of intelligence.

If you do not, you will see what God has willed.” 14 Letter sent from Hulagu Khan (1218–1265) to Baghdad’s last Abbasid Caliph in 1258.

For their own safety,

Baghdad Zoo workers suspend feeding the animals in early April 2003.

Fedayeen Saddam troops take up defensive positions around the zoo.

Eight days after the 2003 invasion,

only thirty-five of the 650 animals in the facility are still alive.

“Here is my letter to the US President

Dear Mr. President,

I know the President himself will be too busy to read this,

but I hope one of his aides or advisors will read and pass the message.

I am writing to you regarding the occupation

of Iraq’s People’s National Stadium in Baghdad,

which has been surrounded by tanks

and is currently being used as a base for US forces.

The local population has time and time again asked them to move

and with Iraq’s Olympic team hoping return to international competitions,

the US presence at the stadium has disrupted training for the current players,

who since the war have not train or participated in any matches.

I call for the US forces to relocate their forces to another position

that is not in anyway occupying the Iraq’s People’s National Stadium.” 15 Posted by www.IraqSport.com to www.aliraqi.org, June 6, 2003.

Miniature of Rifat Chadirji in 2010

re-proposing the same Monument to the Unknown Soldier

to be installed in its original location.

It is to replace an abstract [green] sculpture

installed by the “Survivors’ Group.”

×